JULY 1, 2013

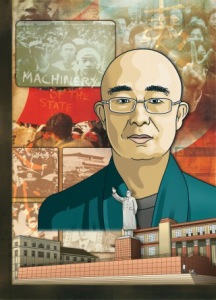

Liao Yiwu was imprisoned from 1990 to 1994, after reciting a poem, “Massacre,” in memory of dead pro-democracy protesters.

CREDIT ILLUSTRATION BY PETER AND MARIA HOEY

Spending time in jail is no fun anywhere, but each society has its own cultural refinements of misery. The sadistic imagination of Chinese prison authorities, though hardly unique, is often remarkable. But so is that of the inmates themselves, who form their own hierarchies, their own prisons within prisons.

At the Chongqing Municipal Public Security Bureau Investigation Center, for example, also known as the Song Mountain Investigation Center, the cell bosses devised an exotic menu of torments. A few samples:

SICHUAN-STYLE SMOKED DUCK: The enforcer burns the inmate’s pubic hair, pulls back his foreskin and blackens the head of the penis with fire.

Or:

NOODLES IN A CLEAR BROTH: Strings of toilet papers are soaked in a bowl of urine, and the inmate is forced to eat the toilet paper and drink the urine.

Or:

TURTLE SHELL AND PORK SKIN SOUP: The enforcer smacks the inmate’s knee caps until they are bruised and swollen like turtle shells. Walking is impossible.

There are other tortures, too, meted out in a more improvised manner. Liao Yiwu, in his extraordinary prison memoir, “For a Song and a Hundred Songs” (translated from the Chinese by Wenguang Huang; New Harvest), describes the case of a schizophrenic woodcutter who had axed his own wife, because she was so emaciated that he took her for a bundle of wood. The cell boss spikes the woodcutter’s broth with a laxative, and then refuses to let him use the communal toilet bucket, with the result that the desperate man shits all over a fellow-inmate. As a punishment for this disgusting transgression, his face is smashed into a basin. The guards, assuming that he has tried to commit suicide, a prison offense, then work him over with a stun baton.

Alexis de Tocqueville came to the United States in 1831 to study the country’s prison system, and ended up writing “Democracy in America.” Observing the Chinese prison system from the inside, from 1990 to 1994, as a “counterrevolutionary” inmate, Liao Yiwu tells us a great deal about Chinese society, both traditional and Communist, including the impact of revolutionary rhetoric, forced denunciations and public confessions, and, as times have changed since Mao’s misrule, criminal forms of capitalism. He ends his account by saying that “China remains a prison of the mind: prosperity without liberty.”

Liao was incarcerated for writing a poem, “Massacre”—a long stream-of-consciousness memorial to the thousands of people who were killed on June 4, 1989, when the pro-democracy movement was crushed throughout China. The poem, in its English translation by Michael Day, begins as follows: