By EVAN OSNOS May 18, 2014

On a single day this spring – April 30, though it could be any – readers scanning the news on China had reason to be baffled: They learned that China is poised to vault past the United States on a measure of economic dominance, five years sooner than expected (unless it isn’t). They also learned that China is at risk of a grave economic slump, if property prices continue to sink. They learned that world-classgenetic researchers in Shanghai, flush with far-sighted government investment, have collaborated to produce new insight into aging cells. And, lastly, they learned that a Chinese journalist has vanished into detention for daring to acknowledge a date on the calendar that censors consider taboo: the 25th anniversary of the crackdown at Tiananmen Square on June 4.

So, which is it: Is China the world’s next great power or a political antique or an economic powder keg? The answer: Yes. China is so vast and contradictory – home to one-fifth of humanity, with an income gap wider than that between New York and Ghana — that we are tempted to simplify it by resorting to the archetypes that capture one side or another. Writing in China from 2005 to 2013, I’ve certainly done it. (Who among us has not regretted a hasty pun on dragons, bamboo or the color “red”?) In my new book, Age of Ambition: Chasing Fortune, Truth, and Faith in the New China, I set out to produce a portrait of life today that acknowledges the inconsistencies, the contradictions, and the ways that China is changing. Here are five of the hoariest truisms that I found ripe for retirement:

You offered your business card with one hand? God help you. When friends visited me in Beijing, often the first and most emphatic custom they had acquired in preparation was the solemn two-handed delivery. No surprise; search Amazon today for books on business in China, and the offerings tend to promise to “demystify China,” while doing their best to have the opposite effect. Some other oft-repeated advice: Don’t give a Chinese friend a clock or a watch as a gift because it signifies death. Avoid wearing the color red, because it is reserved for brides.

It’s time to put away the pith helmets. China is more familiar and navigable than ever before. One sign that the old myths are threadbare: The Chinese are giving each other so many gift-watches that it’s a leading market for the Swiss, and the industry has suffered during an ongoing crackdown on corruption. (I wouldn’t recommend giving a tabletop clock quite yet because some habits endure.) In China today, people know that foreigners will bear some imprint of their habits. Be polite, sincere, keep an eye out for cues and skip the high-brow Orientalism.

China, you see, is a collective culture. What does it mean that Chinese parents put up with the death of more than 5,000 children in poorly constructed schools in an earthquake in 2008? What lessons can we take from the Olympic ceremony, with its flawless choreography and its drummers in perfect unison?

Not much, actually. It is tempting to imagine that Chinese citizens are willing to bear corruption, or heavy-handed stagecraft, because 2,000 years of Confucian influence has seeded a deep reverence for the group—for government, family and country—over the individual.

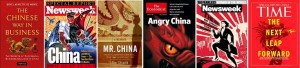

China stereotypes play out visually as well. As this sampling of book and magazine covers would suggest, you can never have too much red or too many dragons when illustrating China – especially when appealing to ideas of an exotic Asian mystique or fears of a rising superpower.

But Chinese culture is not inert. Today, the inclination toward harmony endures, but it competes against the surging force of individual interests. It is a time when the ties between the world’s two most powerful countries, China and the United States, can be tested by the aspirations of a lone peasant lawyer who chose the day and the hour in which to alter his fate. When the Chinese public bears conditions that seem unbearable, it is driven less by culture than by crushing poverty or the threat of force.

Evan Osnos is a staff writer at The New Yorker and the author of Age of Ambition: Chasing Fortune, Truth, and Faith in the New China (Farrar, Straus, & Giroux), from which this article was adapted.

Chinese students ace standardized tests, but they can’t think creatively. For the second time, students in Shanghai occupy the top spot this year on international tests of reading, science and math. The news inspires complaints about American performance (U.S. students scored near or below average) and criticism that one of China’s richest cities doesn’t reflect the gaps across the country.

True, but the headlines miss a deeper change: Chinese parents are looking beyond rote learning in search of alternative education that promotes critical thinking and creativity. When I went to Europe with first-time Chinese tourists, a mother, Zeng Liping, told me that teachers had frowned upon her taking her sixth grader. “Before every school vacation, the teachers tell them, ‘Don’t go out. Stay at home and study, because very soon you’ll be taking the exam to get into middle school.’” But Zeng’s generation has evolving priorities. She quit a stable job as an art teacher and put her savings into starting a fashion label. “My bosses all said, ‘What a shame that you’re leaving a good workplace.’ But I’ve proved to myself that I made the right choice.”

The only people in China who care about dissidents like Ai Weiwei are foreign correspondents. Why, I am often asked, do foreign correspondents devote a disproportionate share of their column inches to the quixotic struggles of lawyers, intellectuals and eccentrics who challenge a government that, for all its faults, has allowed more people in history to climb out of poverty?

Here’s why: Popularity is a poor way to measure the impact of an idea in a country that censors ideas. In the case of Ai Weiwei, for instance, a team of Harvard researchers foundthat news of the dissident artist’s arrest in 2011 was one of the most heavily censored items of the year, which undermines the idea that people in China paid no attention to his arrest. Ai Weiwei’s way of life is emphatically outside the mainstream – he speaks English, poses in nude photos, makes music videos—but his arguments have anticipated ideas that are broadly felt: His attempts to recognize the children killed in collapsing schools was driven by a deep sense of injustice that was among the most common complaints voiced by ordinary Chinese, not just by the urban elite. When he protested a government decision to teardown his studio, in retaliation for his activism, he was giving voice to resentment to arbitrary demolitions that is widely felt.

There is an obvious danger in overstating the impact of dissent in China, but ignoring it blinds us to risks and vulnerabilities that will shape China’s future no less profoundly as its strengths.

China’s economy is doomed to collapse! (Unless it takes over the world!) The larger China looms in the American mind, the more we see it as a caricature, bound to fail or destined to dominate. Four years ago, when China’s GDP was growing at 10 percent per year, it was unfashionable to draw attention to its economic weakness. Today, with debt rising and growth falling, optimism is too often written off as naïve. (The calmest voices are betting that China will muddle through.)

The larger point is that we should retire the choice between absolutes. The story of China in the 21st century is often told as a contest between East and West, between state capitalism and the free market. But in the foreground there is a more immediate competition: the struggle to define the idea of China.Understanding China requires not only measuring the light and heat thrown off by its incandescent new power, but also examining the source of its energy—the men and women at the center of China’s becoming.

Evan Osnos is a staff writer at The New Yorker and the author of Age of Ambition: Chasing Fortune, Truth, and Faith in the New China (Farrar, Straus, & Giroux), from which this article was adapted.

From Politico

http://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2014/05/five-myths-about-china-that-im-sorry-i-helped-spread-106684.html#ixzz32CwpNsSF