By DIDI KIRSTEN TATLOW MAY 19, 2014, 8:26 AM

Cui Jinze stands below the hanging lotus gate at No. 33 Lingjing Lane. The empty rectangles along the top of the gate show where thieves removed carved panels in January.

Courtesy of Cui Jinze

As a 10-year-old boy, Cui Jinze remembers sitting on the desk of his grandfather, a local Communist Party official in Daxing, on Beijing’s southern outskirts, entranced by a map on the wall that marked the city’s palaces, temples and libraries with the character “gu” (古), or “ancient.”

As a teenager, Mr. Cui would visit the sites. “Ever since I was a kid I have been passionate about historical architecture,” Mr. Cui said. “Wherever I went I would mark it on the map,” adding new marks for discoveries that were not notated. “My mother kept it. It’s full of pencil marks. She has it to this day.”

Last week, Mr. Cui, 30, scored a rare victory for what he loves when he won protected status for what remains of two historic courtyard homes, at 33 and 37 Lingjing Lane, and a coveted “hanging lotus gate” within. No. 33 was the home of Chen Baochen, a poet and tutor of Puyi, the last emperor of the Qing dynasty. An assistant minister in the Board of Rites before the 1911 Republican revolution, Mr. Chen was a Qing loyalist and was depicted in the 1987 film “The Last Emperor.” The adjacent courtyard, No. 37, also features historically significant architecture and was connected to No. 33 after 1949.

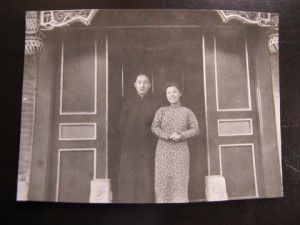

Lin Tao and his wife at the hanging lotus gate of No. 33 Lingjing Lane in the early 1940s. Mr. Lin was a grandson of Lin Kaimo, whose family shared the courtyard with Chen Baochen’s family.

Courtesy of Lin Ming

Importantly, Mr. Cui is the first private citizen in Beijing to have won protected status for a site from the government, according to Chinese media reports quoting cultural affairs officials in Xicheng District, where the homes are located. And the success was the result of independent sleuthing by Mr. Cui, who uncovered an error in the official records, said a fellow researcher, Radium Tam of the Cultural Heritage Conservation Center at Tsinghua University in Beijing.

On May 6, after a 14-month application process, the Xicheng Culture Committee officially informed Mr. Cui it was declaring the two sites “immobile cultural objects,” a status that confers protection, Legal Evening News reported. Although the Ministry of Culture had issued regulations in 2009 allowing citizens to apply, scores of people who did so had failed.

So Mr. Cui’s achievement marks a highly symbolic victory against the apparently relentless transformation of Beijing from a city once suffused with valuable Ming and Qing dynasty architecture to one of generic districts of broad highways and mirrored high-rises. For years, communities have been emptied out and avenues and grand projects rammed through, in a transformation that somewhat parallels the changes wrought by Robert Moses, the “Master Builder,” on New York in the last century — except that the fabric of Beijing was hundreds of years older. Mr. Moses was credited with imposing a sweeping vision on the city but also blamed for ripping out the heart of neighborhoods. Where New York’s transformation was led by one man, in Beijing a largely faceless consortium of power brokers — officials, developers and, sometimes, local residents who want to be relocated for money — are pushing it.

Standing at No. 33, Mr. Cui shared his happiness — and his concerns. For his victory is partial, and contradictory.

A large, eastern section of No. 33, built by 1750 “at the latest,” was knocked down last year to build a community center. A pine tree stands on the razed site, a blue tarpaulin tamping down the rubble. Mr Cui said the local government told him it was knocked down because there were no records identifying it as historically valuable. What records were available incorrectly put Mr. Chen’s home at another address.

Despite that loss, the story is also an inspiring one, spurred by the quest of two young Chinese conservationists to catalog hanging lotus gates, a little-studied facet of traditional architecture, said Ms. Tam — who wrote her college graduation thesis on the gates.

No. 33 was home to two large families, Mr. Chen’s and that of his brother-in-law, Lin Kaimo. (The two men married sisters.) Mr. Lin’s descendents in the United States and Beijing helped Mr. Cui identify the home, supplying historical documentation and photographs.

A son of Mr. Lin, Lin Shizhen, was an architectural historian who restored the precious gate in the courtyard in the 1930s. “So this isn’t just about the value of an old residence, but is also testimony to historical efforts to protect old buildings,” Mr. Cui told the Daily News, part of the Tianjin Daily group.

Determined to find out how many gates were out there, 2012, Mr. Cui and Ms. Tam began consulting records and poring over Google Earth maps of Beijing to determine where the structures, which were inside walled compounds, might be found, based on the size and outline of the buildings. They lie on the central axis of a courtyard, giving them great cosmological significance, said Ms. Tam.

“Even the main gate is not on the central axis,” she said.

She estimates that she has visited more than 200 sites in Beijing that have them, and that there may be up to 300 in the city, but no one can be entirely sure.

“It symbolizes a higher class of courtyard,” said Ms. Tam. “The owner had a fortune or was an official.”

“It is also the symbol of the division between the rather more private sphere of a home and the public sphere,” she said. Only intimate guests could advance beyond the gate. Others were kept outside. “So it had a symbolic as well as a practical function. And it’s very beautiful.”

Yet saving No. 33 and its gate would always be a race against time before the wrecker’s hammer — or the thieves — arrived. This time, Mr. Cui was partly beaten by both, but he stressed it was his first victory at all.

In January, nearly a year after submitting the application for protection to the local authorities, including his research at the Beijing Municipal Archives that proved that the site had been Mr. Chen’s home, someone cut out the wooden panels on top of the gate and stripped off some other decorations. The site remains unprotected.

“Probably they’re on sale now in Panjiayuan” — Beijing’s antiquities market, Mr. Cui said.

No. 37 is designated to be razed to build a primary school and what is left of both sides may yet be moved, despite their new status. Officials are believed to be debating a plan to relocate hundreds of historical sites in Beijing, both to save the buildings and to open the land to developers.

Many valuable traces of historic architecture remain, overlaid with a medley of brick, concrete and corrugated iron structures that once housed workers of the Beijing Railway Bureau and are now home to a variety of people. Amid the crazy palimpsest of slum-like buildings are ancient covered corridors, columns and roofs, the wood sometimes split, the red, green and blue paint peeling. Atop one building, a man tends a pigeon coop from where snow-white birds rise to execute elliptical sweeps over the rooftops, the whistles on their legs playing haunting, wind-like music, above the roar of traffic.

Why did Mr. Cui’s application succeed where so many others failed?

Several reasons, said the graduate of Peking University’s School of Archeology and Museology, who works at an art exhibition company.

“It could be rigorous historical research with incontrovertible evidence, pressure from public opinion, media reports, speeches, Weibo, my personal sense of responsibility in meeting with a local political leader who also graduated from the school of archaeology in Peking University,” Mr. Cui wrote in an email.

Over all, he feels deeply ambiguous about the plan to move historical sites. It’s unclear where they may be moved to, but a “culture park” farther away from the city center is one possibility.

Although relocation can preserve the structures, he said, it robs them of authenticity by removing the physical context. But he that predicted a wave of “preservation-by-relocation” was about to hit China, a way of reconciling, however imperfectly, the interests of conservationists and rapacious developers.

With so much of Beijing’s imperial and Republican-era architecture already torn down, ultimately he believes it’s better to relocate what remains than to see the imperial city’s heritage ground to dust.

“Even though I’ve been faced with so many failures, when you see a building finally knocked over that you tried so hard to save, you still cry.”

From http://sinosphere.blogs.nytimes.com/2014/05/19/a-rare-partial-victory-in-saving-remnants-of-old-beijing/?_php=true&_type=blogs&smid=tw-share&smv2&_r=0