回首當年 學人風采

当2022年11月傳來林毓生先生辭世噩耗時,震駭之餘,筆者陷入了一段長時間的麻木,揮之不去。這幾年,太多的師長朋輩突然故去,尤其是2021年余英時先生,緊接著2022年林毓生先生和張灝先生,這三位近四十年來我常常請益的師長相繼離世,如醍醐灌頂,把我灌下冰窟,頭腦一片空白。這個世界怎麼滑向末日了?萬語千言,不知從何說起……?

今天,離林先生過世已近三年,麻木之後,痛定思痛,林先生與筆者個人之間的往事點點滴滴,湧上腦海,是該寫點東西了。

那是1988年夏天,美國威斯康星大学林毓生教授在上海訪問講學,來到筆者主持的文化研究所(屬於華東理工大學,當時名華東化工學院)接受作為文化研究所榮譽教授的聘書,並作了關於現代自由主義的講座。

圖為1988年林毓生先生(左)接受華東理工大學文化研究所榮譽教授聘書,右坐者為林教授夫人宋祖锦女士

1988年林毓生先生在文化研究所做有關現代自由主義講座

年紀稍長的人還記得,八十年代後半期,林毓生在中國知識界已經以嘹亮的自由主義號角知名。當年我已讀過林教授的諸多著述,特別是他與殷海光先生的通信以及對海耶克思想的論述。然私人的過從交往,還是從1988年開始。那是中國思想文化界熱風吹雨的時節。出生瀋陽的林先生,其人身材高大,目光炯炯有神,奔走於京滬之間,兼有北方人的豪爽風與南方人的書卷氣。但與他聊天卻並非輕鬆之事。他總是能從愉快的寒暄很快地轉向沉重而艱澀的學術及歷史話題。林先生不是那種口似懸河滔滔不絕的演說家,而是字斟句酌,一句三停,不時界定概念,謹慎挑選妥當詞句的學者。他深恐有絲毫不確而導人入歧路。林先生在筆者主編的《思想家》上發表文章(見下面附圖),都要親自反复校對,並鄭重叮囑希望不要更改。這種一絲不苟的作派,典型地體現了他那句關於學術研究要“比慢”的令人略感詫異的著名表述。

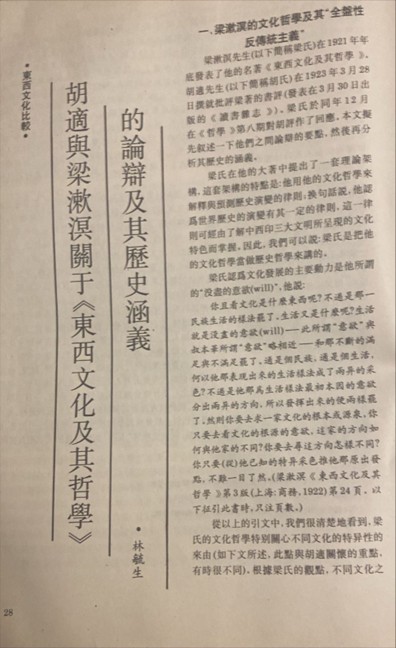

林毓生教授發表在筆者主編的《思想家》雜誌上的文章(1989年1月上海出版)

林教授早年與張灝教授同是台灣大學哲學系殷海光先生的“殷門弟子”。如所周知,所謂“殷門弟子”,是台灣自由中國運動中的一股年輕的中堅力量,在殷海光先生的精神感召下,成為推動台灣社會轉型的學界翹楚。1960年代林毓生赴美在芝加哥大學師從政治哲學家與經濟學家弗里德里希.·海耶克(Friedrich August von Hayek)、社会学家爱德华·希尔斯(Edward Albert Shils)深造,從此成為·海耶克的親炙弟子,並終生服膺其自由主义思想體系。自獲得博士學位後林先生在威斯康星大学麦迪逊分校任教,1994年獲選中華民國中央研究院院士,2004年成为威斯康星大学历史学系荣誉教授。

林毓生先生最顯著的特點,以及他一生孜孜不捨的志業,就是以一種傳教士式的熱忱,深研並傳播海耶克在現代重新啟動的古典自由主義理念。該理念在政治思想上可溯源自蘇格蘭啟蒙運動 {亞當. 斯密(Adam Smith)、休謨 (David Hume)、佛格森 (Adam Ferguson) 為代表} ,在經濟學上則是溯源於孟格(Carl Menger)及維舍(Friedrich Von Wieser)、龐- 巴衛克(Eugen von Bohm-Bawerk)與米塞斯(Ludwig von Mises) 為代表的奧地利學派。

這一脈中間偏右的自由主義思潮(即帶有某種保守主義傾向的自由主義),在1980年代後期以及1992—2013年在非官方的中國知識界話語中,實際上已經佔據了主流地位(如徐友漁、朱學勤、劉軍寧、周其仁、張維迎、高全喜、賀衛方、張鳴、吳稼祥…..等學者)。因此,在2013年之後,遭受到北京當局相當嚴酷的鎮壓,在中國大陸已經很難發聲了。 在此期間,林毓生先生與中國大陸及台灣知識界的交流主要是在美國西方以及台灣香港等地進行的。但林毓生先前在上世紀八十、九十年代的論著及其演說,無疑對中國這種主流的自由主義思潮的興起與擴展有啟迪功能。這種影響,據林先生自述,與1975年他同余英時先生的會面有某種關聯。

在台灣與大陸播撒自由主義種子

1975年,當林毓生教授在美國學界如魚得水並逐漸形成一些自己的系統看法後,在台灣他見到了余英時先生。余先生與他談及旅美的華裔人文學者應該撥出時間用中文撰文的重要性,林先生深以為然,頗有共鳴。林先生說:“就這樣,我開始在1975年用中文撰文。”這是林先生後來成為穿梭於台海兩岸成為自由主義傳道士的重要緣起。

於是,林先生積極把自己的傳教士式的熱忱付諸實踐,人們看到了他自從1975年之後在台海兩岸的匆匆學術之旅。

先是,在暑期返回台灣,在台灣大學歷史系講授「思想史方法論」等一系列學術活動。

隨後,在八十年代及九十年代後期二零一零年代幾次進出中國特別是北京上海,傳播海耶克式自由主義火種。這才有了如前所述於1988年應聘任華東理工學院文化研究所榮譽教授以及後來於2002年被聘為中國美術學院名譽教授之舉。林先生並在中國多個學術單位舉辦演講、講座,在多種刊物報紙上發表論文或各類文章,譬如前述1989年1月在《思想家》雜誌創刊號的《胡適與梁漱溟關於東西文化及其哲學的論辯及其歷史意義》等論文與文章的發表。

1989年天安門事件之後有一段時期,林教授很難再赴中國大陸展開學術活動,但他與海外中國學者作家的交往卻更加頻繁了,特別是我所了解的與普林斯頓中國學社的流亡知識人的交流。

1991年5月3、4、5日林教授參加在普林斯頓大學舉辦的《從五四到河殤》的大型學術研討會,就“西方自由主義對馬克思主義的批評”為題作了長篇學術發言。指出,馬克思主義的根本基本錯誤前提在於,它企圖摧毀過去的文明成果,從零開始以理性設計一整套完美無缺的文明,依恃暴力革命憑空在人間創造一個天堂,結果卻是把世界帶回野蠻,造成了歷史上亙古未有的人類災難。

1995年5月林毓生來普林斯頓中國學社參加《文化中國:轉型期思潮及流派》學術研討會。在會議上,他以充分理據批評了與會幾位新左派學者崔之元、甘陽和王紹光的主張,指出他們所謂“超越社會主義/資本主義兩分法“的所謂”制度創新”勢必導致復辟到暴力革命確立的共產極權制度。

…………

1995年5月林毓生來普林斯頓中國學社參加《文化中國:轉型期思潮及流派》學術研討會期間在筆者家晚餐(左起順時針:林毓生 李澤厚 傅偉勳 金春峰 阮銘 陳奎德 商戈令 蘇曉康)

學術與思想貢獻

林毓生先生用他獨有的清晰、乾淨、有分寸,用『奧卡姆的剃刀(Ockham’s razor)』,刪削掉無關的論述及詞句,不賣弄術語,杜絕陳腐之詞和文藝腔調的行文,成就了他的學術風格。林先生的學術與思想貢獻,除了他在海峽兩岸嚴謹而深入地闡釋海耶克式的自由主義思想精髓,如自由與解放、自由與權威、法治與法制、人權與民權、憲政與極權、法律的普遍性與抽象性、三種不同的「民主」之區分等重要概念的釐清,澄清了多年來瀰漫中國學界的迷霧之外,更重要的是他自己的原創性貢獻。在筆者看來,主要是如下兩點:

1.「全盤性反傳統主義」(Totalistic anti-traditionalism or totalistic iconoclasm)

林先生認為,相較於世界史上的思想運動,20 世紀中國思想史最顯著的特徵之一,是源起於中國五四時代對於中國傳統文化遺產堅決地全盤否定的態度。五四時期全盤化的反傳統主義(又稱整體主義的反傳統主義,totalistic anti-traditionalism),意指「對中國傳統複雜、豐富的內容,不作分辨,直指中國傳統的整體」。其中,傳統儒家思想尤其被認為與中國傳統的其他部分有「必然」的「有機式因果關係」,若要進行中國社會與政治的變革,首先必須徹底改變人們思想和價值,以進一步根除仍盛行於當時的舊傳統。這一以儒家思想為中心目標而對中國傳統整體性攻擊,林毓生描述為「思想決定論的化約主義」,呈現「意識形態」的特徵──意味著持全盤化的反傳統主義立場的中國知識分子,根據自己的前提,發展出一套封閉性強的「系統性」論述,並以此為基礎,自認不需要對傳統的所有成分加以研究,也無須分梳取捨傳統的不同部分,而直接對傳統採取以思想為中心、整體性地摒棄。

要 解 釋「全盤性反傳統主義」之出現,必須從中國傳統文化找內因:由傳統一脈相承到現代中國知識人的心靈,有一種根深柢固的文化傾向——「藉思想、文化以解決問題的方法」(cultural-intellectualistic approach),這是一種簡單化、一元論的思想方法,其根本信念是預設思想、觀念以至文化的改變是一切變革的根本,將思想與行動之間的關係視為密切的、甚至是同一的關係。它有潛在演變成「惟思想的、整體主義的思想模式」(intellectualistic-holistic mode of thinking)的可能性,即是將社會文化視為一個受思想主導影響的有機整體 。林教授認為,儘管五四時期的反傳統主義者在思想內容上反對傳統,但其思想模式仍受到傳統的支配。這種把反傳統歸咎於傳統的論點當年極具震撼性。

2.「文化傳統的創造性轉化」(creative transformation)

「創造性轉化」一詞,在現代臺灣與中國大陸曾激起熱烈討論,其源自林毓生探討五四時期整體反傳統的「中國意識的危機」而起。林教授自己在《思想與人物一書中曾解釋說:“這幾年,偶爾看到國內有人引用,在一份有關[文化復興]半官式文告中也曾出現(事實上,我說的『創造性的改進』或「創造的轉化」必須與[文化復興]之所指,做一嚴格的區分。)這幾個字大有變成口號的危險了。但,究竟什麼是文化傳統的「創造性轉化」呢?那是把一些中國文化傳統中的符號與價值系統加以改造,使經過改造的符號與價值系統變成有利於變遷的種子,同時在變遷的過程中繼續保持文化的認同。這是無比艱苦而長遠的工作;不是任何一個人、一群人或一個時代的人所能達成的。……可惜的是,自五四以來,因為知識界的領袖人物,「多會呼叫,少能思想」,他們的學養與思想的根基太單薄,再加上左右政治勢力的分化與牽制,所以「中國的學術文化思想,總是在復古、反古、西化、反西化或拼盤式的折衷這一泥沼里打滾,展不開新的視野,拓不出新的境界」。”

由於林毓生與五四之父與子胡適、殷海光皆有密切關係,以自由主義者自詡,因此「創造性轉化」對於五四自由主義的深化探討有實質性的貢獻,也充滿了知識人的現實關懷。然而,林毓生對於五四激進的各式思想,包括當年的自由主義有著強烈的批判,但又要從有限的歷史資源中,尋求解決歷史與現實糾結的問題。「創造性轉化」無疑是其提供的主要藥方之一。是耶非耶,能否有效?尚待歷史之驗證。但無論如何,從它的巨大反響觀之,林先生無疑深化了有關中國自由主義的討論,這本身已經是創造性的成果了。

{注:以上概述,出自林毓生著《中國意識的危機》Lin Yü-sheng, The Crisis of Chinese Consciousness: Radical Anti-traditionalism in the May Fourth Era (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1979) 和《思想與人物》(台北,1983;2009年東亞出版人會議選為“東亞經典100本”之一) 以及《二十世紀中國激進化反傳統思潮、中式馬列主義與毛澤東的烏托邦主義》}

林毓生先生致力批評的「全盤性反傳統主義」和強烈主張的「文化傳統的創造性轉化」這兩項原創性的學術思想貢獻,引發了廣泛的反響和讚譽,當然也激發了強烈的商榷和批評。有鑑於此,林先生的的這些思想學術創獲無疑將留在二十世紀中國自由主義思想史上。

林毓生先生留下的學術遺產,計有:The Crisis of Chinese Consciousness: Radical Anti-traditionalism in the May Fourth Era(Madison,1979),中譯本《中國意識的危機》(貴州,1986;修訂再版1988)、《思想與人物》(台北,1983;2009年東亞出版人會議選為“東亞經典100本”之一)、《政治秩序與多元社會》(台北,1989)、《熱烈與冷靜》(上海,1998)、《殷海光 林毓生書信錄》(合著)重校增補本(吉林,2009)、《中國傳統的創造性轉化》、《林毓生思想文選》(上海,2011年)、《中國激進思潮的起源與後果》(吉林,2012年)、《現代知識貴族的精神:林毓生思想近作選》等。

2022年11月22日,林毓生先生在美国丹佛市離我們而去了。他一生風塵僕僕,穿行於台灣、美國和中國大陸三地,孜孜以求自由法治人權憲政在東亞那一片古老的土地上生根發芽,開花結果。林先生殫精竭慮,以赤子之心,放言神州,洪鐘大呂,擲地有聲,成為迴響在台海兩岸的自由鐘聲。他的一生行止,令我想起了其先師殷海光對林毓生業師海耶克的評價:一開局就不同凡響:氣象籠罩著這個自由世.界的存亡,思域概括著整個自由制度的經緯。如今,一個甲子過去,一個籠罩自由制度存亡的嶄新局面之曙光正在遠東的天邊若隱若現。我想,林先生一定比我們更加洞悉先兆的,他可以在九泉之下安息了。

The Resonance of the Bell of Freedom Across the Taiwan Strait

— In Memory of Professor Yusheng Lin

By Kuide Chen Ph.D.

Looking Back at the Scholar’s Grace

When the grievous news of Professor Yusheng Lin’s passing came in November 2022, I was stunned and subsequently sank into a prolonged numbness that I could not shake off. In recent years, too many of my teachers and peers have suddenly passed away. In particular, in 2021 Professor Yingshi Yu, followed closely in 2022 by Professors Yusheng Lin and Hao Zhang—three mentors from whom I had sought advice for nearly four decades— all departed one after another. It felt as if a cold bucket of ice water had been poured over me, leaving my mind utterly blank. Was the world sliding toward its end? With countless words on my mind, where could I even begin…? Now, nearly three years after Professor Lin’s passing, as the numbness has given way to reflection, memories of the many moments between him and myself have surged back. It is time to write something down.

It was the summer of 1988. Professor Yusheng Lin of the University of Wisconsin visited Shanghai and came to the Institute of Cultural Studies, which I directed (then under East China University of Chemical Technology, today’s East China University of Science and Technology). There, he accepted an appointment as Honorary Professor of the Institute and gave a lecture on modern liberalism.

Photo: In 1988, Professor Yusheng Lin (left) accepted the Honorary Professorship of the Institute of Cultural Studies at East China University of Science and Technology. On the right is his wife, Zujin Song.

In 1988, Professor Yusheng Lin delivering a lecture on modern liberalism at the Institute of Cultural Studies.

Those of slightly older generations may remember that, in the latter half of the 1980s, Yusheng Lin had already become widely known in Chinese intellectual circles as a resounding voice for liberalism. By then, I had already read many of his writings, especially his correspondence with Professor Haiguang Yin and his discussions on Friedrich Hayek’s thought. Yet our personal acquaintance began only in 1988, during those stormy and fervent years in China’s intellectual and cultural scene. Born in Shenyang, Professor Lin was tall and imposing, with piercing eyes. Moving between Beijing and Shanghai, he combined the forthrightness of a Northerner with the literary refinement of a Southerner. But chatting with him was by no means light or casual. He could shift quickly from cheerful greetings to weighty and abstruse topics in scholarship and history. He was not a fast-talking orator with a glib tongue, but a scholar who chose words with great care, weighing every sentence, constantly defining concepts and cautiously selecting precise terms. He feared that even the slightest imprecision might mislead others down the wrong path. Whenever he published in Thinker—a journal I edited (see illustration below)—he would personally proofread the articles repeatedly and solemnly requested that no changes be made. This meticulous approach embodied his well-known and somewhat surprising dictum about scholarship: that it must “err on the side of slowness.”

Article by Professor Yusheng Lin published in Thinker, edited by the author (January 1989, Shanghai). ——-Article: The Debate between Shi Hu and Shuming Liang on Eastern and Western Cultures and Their Philosophies and Its Historical Implications

Professor Lin, together with Professor Hao Zhang, had been a disciple of Professor Haiguang Yin at The Department of Philosophy, National Taiwan University. As is well known, the so-called “disciples of Yin” formed a vigorous young force in Taiwan’s Free China movement, who, inspired by Professor Yin’s spirit, became leading figures in steering Taiwan’s social transformation. In the 1960s, Lin went to the United States and studied at the University of Chicago under political philosopher and economist Friedrich August von Hayek and sociologist Edward Albert Shils. From that point, he became a close disciple of Hayek and a lifelong adherent to his system of liberal thought. After earning his doctorate, Lin taught at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. In 1994, he was elected an Academician of Academia Sinica, and in 2004, he became Professor Emeritus in the Department of History at the University of Wisconsin.

The most remarkable trait of Professor Lin, and the life mission he pursued tirelessly, was his almost missionary zeal in studying and disseminating Hayek’s revival of classical liberalism in modern times. This intellectual lineage, in political thought, can be traced back to the Scottish Enlightenment (represented by Adam Smith, David Hume, and Adam Ferguson), and in economics, to the Austrian School (Carl Menger, Friedrich von Wieser, Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk, and Ludwig von Mises).

This center-right strain of liberalism—liberalism with a certain conservative inclination—had by the late 1980s and especially between 1992 and 2013 become the mainstream discourse in China’s unofficial intellectual circles (with scholars such as Youyu Xu, Xueqin Zhu, Junning Liu, Qiren Zhou, Weiying Zhang, Quanxi Gao, Weifang He, Ming Zhang, Jiaxiang Wu, among others). Consequently, after 2013 it faced severe suppression by Beijing authorities, making it nearly impossible to be voiced on the mainland. During this period, Professor Lin’s exchanges with intellectual circles in mainland China and Taiwan primarily took place in the West, Taiwan, and Hong Kong. Nevertheless, his writings and speeches from the 1980s and 1990s undoubtedly helped inspire and nurture the rise and expansion of this mainstream liberal trend in China. According to Lin himself, this influence was in some way related to his meeting with Professor Yingshi Yu in 1975.

Sowing the Seeds of Liberalism in Taiwan and Mainland China

In 1975, after Professor Yusheng Lin had found his footing in American academia and gradually developed some of his own systematic views, he met Professor Yingshi Yu in Taiwan. Yu emphasized to him the importance of overseas Chinese scholars in the humanities setting aside time to write in Chinese. Lin agreed wholeheartedly and resonated deeply. He later recalled: “That is how I began writing in Chinese in 1975.” This became the starting point for Lin’s subsequent role as a messenger of liberalism, shuttling across the Taiwan Strait. Thus, Lin put his missionary zeal into practice, and people soon witnessed his tireless academic journeys across the Taiwan Strait after 1975.

First, he returned to Taiwan during summers, where he gave lectures at the Department of History, National Taiwan University, including courses on “Methodology of Intellectual History” and other academic activities.

Subsequently, during the 1980s, late 1990s, and 2010s, he made several visits to China—particularly Beijing and Shanghai—where he spread the sparks of Hayekian liberalism. This included, as mentioned earlier, his appointment in 1988 as Honorary Professor at the Institute of Cultural Studies of East China University of Chemical Technology, and later, in 2002, as Honorary Professor at the China Academy of Art. Professor Lin also delivered lectures and talks at multiple Chinese academic institutions and published papers and articles in various journals and newspapers. For instance, he published “The Debate between Shi Hu and Shuming Liang on Eastern and Western Cultures and Philosophies and Its Historical Significance” in the inaugural issue of Thinker in January 1989.

After the Tiananmen Incident in 1989, for a time it became difficult for Professor Lin to travel to mainland China for academic activities. However, his interactions with overseas Chinese scholars and writers became even more frequent, especially his exchanges with exiled intellectuals of the Princeton China Initiative, which I personally witnessed.

On May 3–5, 1991, Professor Lin participated in the large-scale academic conference From May Fourth to River Elegy held at Princeton University. There, he delivered a long academic speech on “The Critique of Marxism by Western Liberalism.” He pointed out that the fundamental and fatal flaw of Marxism lies in its attempt to destroy all past civilizational achievements and start anew by rationally designing a flawless civilization. It relies on violent revolution to conjure up a paradise on earth from nothing, but the actual result is a return to barbarism and the creation of an unprecedented human catastrophe in history.

In May 1995, Professor Yusheng Lin attended the academic conference Cultural China: Intellectual Trends and Schools of Thought in a Time of Transformation, hosted by the Princeton China Initiative. At the conference, he sharply and rigorously criticized the positions of several new-left scholars, including Zhiyuan Cui, Yang Gan, and Shaoguang Wang. He argued that their so-called “institutional innovations” designed to “transcend the dichotomy of socialism and capitalism” would inevitably lead back to the communist totalitarian system established through violent revolution.

During the May 1995 academic conference Cultural China: Intellectual Trends and Schools of Thought in a Time of Transformation at the Princeton China Initiative, Professor Yusheng Lin at a dinner gathering at the author’s home. Clockwise from left: Yusheng Lin, Zehou Li, Weixun Fu, Chunfeng Jin, Ming Ruan, Kuide Chen, Geling Shang, Xiaokang Su.

Academic and Intellectual Contributions

Professor Yusheng Lin developed a unique scholarly style—clear, precise, and measured. Employing “Ockham’s razor” to cut away irrelevant arguments and superfluous words, he avoided pedantic jargon, shunned stale expressions, and rejected ornate literary tones. His academic and intellectual contributions extended beyond his rigorous and in-depth explications of the essence of Hayekian liberal thought across the Taiwan Strait. He clarified key concepts such as liberty and liberation, liberty and authority, rule of law and rule by law, human rights and civil rights, constitutionalism and totalitarianism, the universality and abstraction of law, and the distinctions between three different types of “democracy.” By doing so, he dispelled much of the confusion that had long clouded Chinese academia. Even more importantly, he made original contributions of his own. In my view, they can be summarized primarily in two respects:

1,“Totalistic Anti-Traditionalism” (or Totalistic Iconoclasm)

Professor Yusheng Lin believed that, compared with intellectual movements in world history, one of the most striking features of twentieth-century Chinese intellectual history was the resolute and total denial of China’s traditional cultural heritage that emerged during the May Fourth era. The May Fourth period’s totalistic anti-traditionalism also called holistic anti-traditionalism—meant “directly targeting the entirety of Chinese tradition, without distinguishing among its rich and complex elements.” Traditional Confucian thought was especially seen as hav_ing an “inevitable” and “organically causal relationship” with other parts of Chinese tradition. Therefore, to transform Chinese society and politics, it was thought necessary first to thoroughly change people’s ideas and values, so as to eradicate the old traditions still prevalent at that time. This comprehensive attack on Chinese tradition, with Confucianism as its central target, was described by Lin as a form of “intellectual determinism reductionism,” bearing the features of an “ideology.” That is, Chinese intellectuals who adopted a totalistic anti-traditionalist stance developed, based on their own premises, a closed “systematic” discourse. On this basis, they believed they had no need to study the various components of tradition, nor to distinguish and select among its different parts, but could instead reject tradition as a whole in an ideologically comprehensive manner centered on ideas.

To explain the emergence of “totalistic anti-traditionalism,” one must seek internal causes within Chinese traditional culture. From tradition through to modern Chinese intellectuals’ minds, there had been a deeply rooted cultural tendency—what Lin called a “cultural-intellectualistic approach,” that is, a method of seeking solutions through ideas and culture. This is a simplified, monistic way of thinking, whose fundamental belief presupposes that changes in thought, ideas, and culture constitute the foundation of all transformation. It views the relationship between thought and action as close—even identical. This tendency contains the potential to evolve into what Lin termed an “intellectualistic-holistic mode of thinking,” which conceives of social culture as an organic whole directed and dominated by ideas. Professor Lin argued that, although the anti-traditionalists of the May Fourth era opposed tradition in terms of content, their mode of thought was still shaped by tradition. This argument— attributing anti-traditionalism itself to tradition—was profoundly shocking at the time.

2,“Creative Transformation” of Cultural Tradition

The concept of “creative transformation” once stirred intense debate in both modern Taiwan and mainland China. It originated from Yusheng Lin’s exploration of totalistic anti-traditionalism in The Crisis of Chinese Consciousness. In his book Intellectuals and the Chinese Cultural Tradition, Lin explained: “In recent years, I occasionally saw this phrase quoted domestically, and it even appeared in a semi-official proclamation about ‘cultural renaissance.’ (In fact, what I referred to as ‘creative improvement’ or ‘creative transformation’ must be strictly distinguished from what is meant by ‘cultural renaissance.’) These few words run the risk of turning into a mere slogan. But what, after all, is the ‘creative transformation’ of cultural tradition? It is to adapt certain symbols and value systems within Chinese cultural tradition, so that these adapted symbols and values become seeds conducive to change, while at the same time preserving cultural identity during the process of transformation. This is an arduous and long-term task; it cannot be achieved by any single individual, group, or even an entire era… Unfortunately, since the May Fourth era, because the leading figures of the intellectual world ‘are more inclined to shout slogans than to think,’ their scholarly cultivation and intellectual foundations have been too weak. Coupled with the divisions and constraints imposed by both the left and the right political forces, Chinese academic and cultural thought has always been stuck in the quagmire of revivalism, anti-traditionalism, Westernization, anti-Westernization, or eclectic patchwork, unable to open new horizons or expand into new realms.”

3,“Creative Transformation” of Cultural Tradition

The concept of “creative transformation” once stirred intense debate in both modern Taiwan and mainland China. It originated from Yusheng Lin’s exploration of totalistic anti-traditionalism in The Crisis of Chinese Consciousness. In his book Intellectuals and the Chinese Cultural Tradition, Lin explained: “In recent years, I occasionally saw this phrase quoted domestically, and it even appeared in a semi-official proclamation about ‘cultural renaissance.’ (In fact, what I referred to as ‘creative improvement’ or ‘creative transformation’ must be strictly distinguished from what is meant by ‘cultural renaissance.’) These few words run the risk of turning into a mere slogan. But what, after all, is the ‘creative transformation’ of cultural tradition? It is to adapt certain symbols and value systems within Chinese cultural tradition, so that these adapted symbols and values become seeds conducive to change, while at the same time preserving cultural identity during the process of transformation. This is an arduous and long-term task; it cannot be achieved by any single individual, group, or even an entire era… Unfortunately, since the May Fourth era, because the leading figures of the intellectual world ‘are more inclined to shout slogans than to think,’ their scholarly cultivation and intellectual foundations have been too weak. Coupled with the divisions and constraints imposed by both the left and the right political forces, Chinese academic and cultural thought has always been stuck in the quagmire of revivalism, anti-traditionalism, Westernization, antiWesternization, or eclectic patchwork, unable to open new horizons or expand into new realms.” ·

Because of Lin’s close intellectual relationships with Shi Hu, Haiguang Yin, and other figures—men who were regarded as fathers of the May Fourth Movement—and because of his own identity as a self-proclaimed liberal, the idea of “creative transformation” made a substantive contribution to the further exploration of May Fourth liberalism, while also embodying an intellectual’s deep concern for reality. Nevertheless, Yusheng Lin maintained strong critiques of the various radical ideologies of the May Fourth period, including even the liberalism of that era. At the same time, he sought ways to resolve the entanglement between history and reality within the limits of available historical resources. “Creative transformation” was undoubtedly one of the main remedies he proposed. Whether it is truly effective or not remains to be tested by history. But regardless, judging from its enormous impact, Professor Lin unquestionably deepened the discussion of Chinese liberalism—and that in itself was a creative achievement.

(Note: The above summary is drawn from Yusheng Lin’s works: The Crisis of Chinese Consciousness: Radical Anti-Traditionalism in the May Fourth Era (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1979); Intellectuals and the Chinese Cultural Tradition (Taipei, 1983; se_lected in 2009 by the East Asian Publishers’ Conference as one of the “100 East Asian Classics”); and Twentieth-Century China’s Radical Anti-Traditionalist Trends, Sinicized Marxism, and Mao Zedong’s Utopianism. )

Professor Yusheng Lin’s devoted critiques of “totalistic anti-traditionalism” and his strong advocacy of “creative transformation of cultural tradition” stand as two original scholarly contributions that elicited widespread response and acclaim, while also provoking heated debate and criticism. In light of this, there is no doubt that these intellectual achievements will remain firmly inscribed in the history of twentieth-century Chinese liberal thought.

The scholarly legacy Professor Lin left behind includes: The Crisis of Chinese Consciousness: Radical Anti-Traditionalism in the May Fourth Era (Madison, 1979); its Chinese translation The Crisis of Chinese Consciousness (Guizhou, 1986; revised edition 1988); Intellectuals and the Chinese Cultural Tradition (Taipei, 1983; se_lected in 2009 by the East Asian Publishers’ Conference as one of the “100 East Asian Classics”); Political Order and Pluralistic Society (Taipei, 1989); Passion and Reason (Shanghai, 1998); The Correspondence of Haiguang Yin and Yusheng Lin (co-authored, revised and expanded edition, Jilin, 2009); Creative Transformation of Chinese Tradition; Se_lected Writings of Yusheng Lin (Shanghai, 2011); The Origins and Consequences of China’s Radical Ideological Currents (Jilin, 2012); and The Spirit of the Modern Intellectual Aristocracy: Se_lected Recent Writings of Yusheng Lin, among others.

On November 22, 2022, Professor Yusheng Lin passed away in Denver, Colorado. Throughout his life, he journeyed tirelessly between Taiwan, the United States, and mainland China, persistently striving for the rooting, blossoming, and fruition of freedom, the rule of law, human rights, and constitutionalism on that ancient land of East Asia. With tireless effort and a pure heart, he spoke out boldly across China. His voice was like a great bell of freedom, resonating powerfully across the Taiwan Strait. His life and work remind me of the words of his own teacher, Haiguang Yin, in his assessment of Lin’s mentor, Friedrich Hayek: “From the very outset, he was extraordinary. His vision encompassed the very survival of the free world; his intellectual domain summarized the warp and weft of the entire liberal order.” Now, sixty years later, a new dawn, one enveloping the survival of the liberal order, seems to be faintly emerging on the horizon of the Far East. I believe Professor Lin must have perceived this premonition far more clearly than we can. He may now rest peacefully beneath the Nine Springs.

—— 转载自《自由鐘》雙月刊雜誌2025年九月號

刊登日期: 2025-09-10 19:47:13