A civil servant explains the growth model, ‘Likonomics’ and efforts at rebalancing

A civil servant explains the growth model, ‘Likonomics’ and efforts at rebalancing

February 7, 2016: The Chinese growth story has spawned a number of books; all seeking to interpret or criticise or praise or even forecast where the country is headed. Deeply intellectual and yet, at times, giving rise to a suspicion that they are each playing out the dilemma, first spelled out in the Panchatantra, of the seven blind men who had a short meeting with an elephant and spent the rest of their time arguing bitterly about what/who the animal actually resembled.

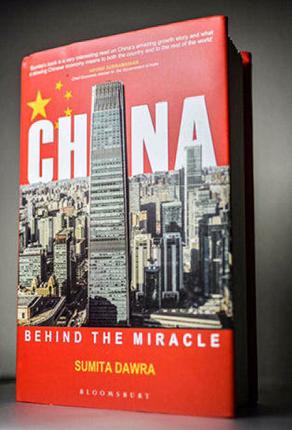

Sumita Dawra has chosen to eschew the standard approach, making this book quite different. The author is a civil servant, who had been posted as the head of the economic wing of the Indian Embassy in Beijing for a little over three years starting early 2011. Her position in Beijingrequired her to accompany various high-powered delegations desiring to study various aspects of the China story: farming practices, SEZs, corporate success stories, port cities, growth poles, urban management, etc. This involved visits to different parts of China, rural and urban, glamorous and underdeveloped.

Economic travelogue

Dawra documents what she saw without putting forth her own point of view. The book also refrains from commenting on politics and ideology. So what you get can well be termed a collage of snapshots — of what she saw, heard and read in government reports/local media — somewhat like a travelogue but focusing more on matters ‘economic’. Herein lies the value.

Consider the period she was there. The Chinese leadership had as early as 2007 (when it was a $2+ trillion dollar economy with a foreign exchange approaching nearly half its GDP) started terming the infrastructure/export-focused growth model as “unstable, unbalanced, uncoordinated and unsustainable” and had indicated Beijing Olympics (2008) and Shanghai Expo (2010) be the milestones post which the economy would become a “harmonious” society in an innovation-centred economy.

These milestones had now passed. Growth rates had already come below the double digit levels of the first decade, and were testing 7.5 per cent by 2012-13. The debate on a hard landing had already started.

Media discussions of the unsustainable debt levels of provincial governments, irregularities of shadow banking, rising stocks of cars and falling house price levels had become common. The phrase ‘Likonomics’ had already come into vogue (as the economic views of Premier Li Keqiang were popularly summarised) to depict the government intent — no direct stimulus in the form of investments to push up growth rates, focus on deleveraging as credit in the economy (growing faster than GDP) had already touched 190 per cent and to carry out structural reform in interest rates, utility pricing, etc.

China had started ‘rebalancing’, readying itself for the ‘new normal’. This is the China she depicts through a kaleidoscope of images.

The book has been organised into 10 chapters, preceded by a well-worded introduction, depicting various aspects of the China story: how Beijing drives the growth model and the ‘compulsions’ of the inter province competition which underlies the dizzying scale and role played by infrastructure, the position, role and pain points of financial liberalisation, the differentiated roles played by the Pearl River and the Yangtze River Delta’s in making China ‘the factory of the world’, etc. What makes China attractive to multinationals, and how culture and tourism are promoted, are also discussed.

The status of health care systems, higher education; the innovative and diverse ways in which agriculture is promoted (including the large-scale models of commercial demonstration of Hydroponics — the science of growing crops and vegetables without using soil) as also glimpses of internationally competitive Chinese corporate’s (in various sectors including solar and e-commerce) all find a place.

Growth pangs

Rapid growth generated its own set of problems. Inequalities sharply widened with attendant issues. The Gini coefficient crossed 0.47 in 2008 as against 0.31 two decades earlier. Regional disparities got aggravated (Western regions have 72 per cent of the landmass, 30 per cent of the population but a sub-20 per cent share of the GDP. The conscious, determined effort to develop these areas since 2000-01 with investment exceeding $500 billion resulted in an average annual growth rate of over 11.6 per cent being experienced in the ensuing 10-year period and yet the absolute gap with the ‘East’ widened).

Over-investment in traditional sectors and infrastructure made growth slowdown inevitable. Readers will get an appreciation of how these issues are sought to be countered. The focus on supporting innovation and entrepreneurship has resulted in creating a service economy of over $5 trillion and new company formation crossing 3.5 million registrations in 2014.

Faster growth in the 12 provinces/municipalities and autonomous areas of the ‘West’ is being targeted through the re-establishment of the trade routes — the ‘one belt, one road’, the ‘maritime silk road’, the ‘Eurasian bridge and the BICM (Bangladesh, India, China, Myanmar) initiatives, etc.

Focus on urbanisation is another strand. While it took Europe 150 years to achieve 50 per cent urbanisation, China did it in 60 and now expects it to touch 60-70 per cent by 2020-30. Case stories depict all these aspects/issues. The author rounds off these depictions with her personal stories of ‘experiencing’ China.

What are the takeaways? If the idea is to ‘form an opinion’, this is not the book. If, however, the idea is to better appreciate the nuances of both sides of a China debate, using a kaleidoscope, like this, it will stand you in good stead.

The reviewer was chairman of Exim Bank of India and is a China specialist

(This article was published on February 7, 2016)