The Story of the Stone is essential reading in China, yet this great work of literature is barely known in the English-speaking world

The Story of the Stone is essential reading in China, yet this great work of literature is barely known in the English-speaking world

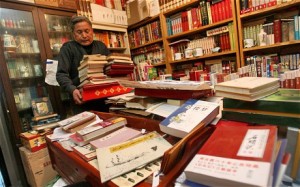

Weighty tomes: Chinese pensioner Zhang Enmao with some of his 1,250 copies of the novel ‘Dream of the Red Chamber’, also known as The Story of the Stone Photo: REX FEATURES

By John Minford7:00PM BST 28 Jul 2012Comments83 Comments

The death of the elderly Chinese scholar Zhou Ruchang, noted recently in a Daily Telegraph obituary, draws attention to a startling fact: that China’s greatest work of literature, the 18th-century novel Dream of the Red Chamber, on which Professor Zhou was an acknowledged – and somewhat obsessive – expert, is still virtually unknown in the English-speaking world. And yet a complete and highly readable English translation has been available in Penguin Classics for nearly 30 years.

In its native land, The Story of the Stone, as the book is also known – Stone for short – enjoys a unique status, comparable to the plays of Shakespeare. Apart from its literary merits, Chinese readers recommend it as the best starting point for any understanding of Chinese psychology, culture and society.

So why is this masterpiece so neglected in the West? Does it just reflect a general decline of interest in literature? Or is there something particular about the Chinese case? Are we, perhaps, too obsessed with China’s latest economic statistics to spare a thought for what’s left of its soul? As one philistine academic colleague growled at me not long ago, “Who cares about Chinese poetry anyway?” In British universities, teachers of traditional Chinese literature are in danger of becoming extinct.

For the Chinese, however, The Story of the Stone is a talisman. Three years ago, Madame Fu Ying, Chinese ambassador to the Court of St James (now deputy foreign minister of the People’s Republic of China, and a rising star), demonstrated this when she presented the complete five-volume Penguin edition to the Queen. On my arrival in China in 1980, I was advised by Yang Xianyi, one of Stone’s Beijing translators, that if ever I found myself in a fix with the authorities, I should mention my own connection with the book. I once tested this theory, with the Public Security Bureau – and it worked.

The book was left unfinished by the author Cao Xueqin at his death in 1763 and was eventually published in 1792, with an added conclusion attributed to Gao E. It is written in high-class Peking vernacular, with many unusual expressions and allusions, necessitating dozens of footnotes per chapter for today’s readers. But despite this, and despite its daunting length (twice as long as War and Peace) and its huge dramatis personae (well over 300 main characters), it is still widely read throughout the Chinese-speaking world. Mention of it triggers an instant gleam of recognition, and opens up new possibilities of communication.