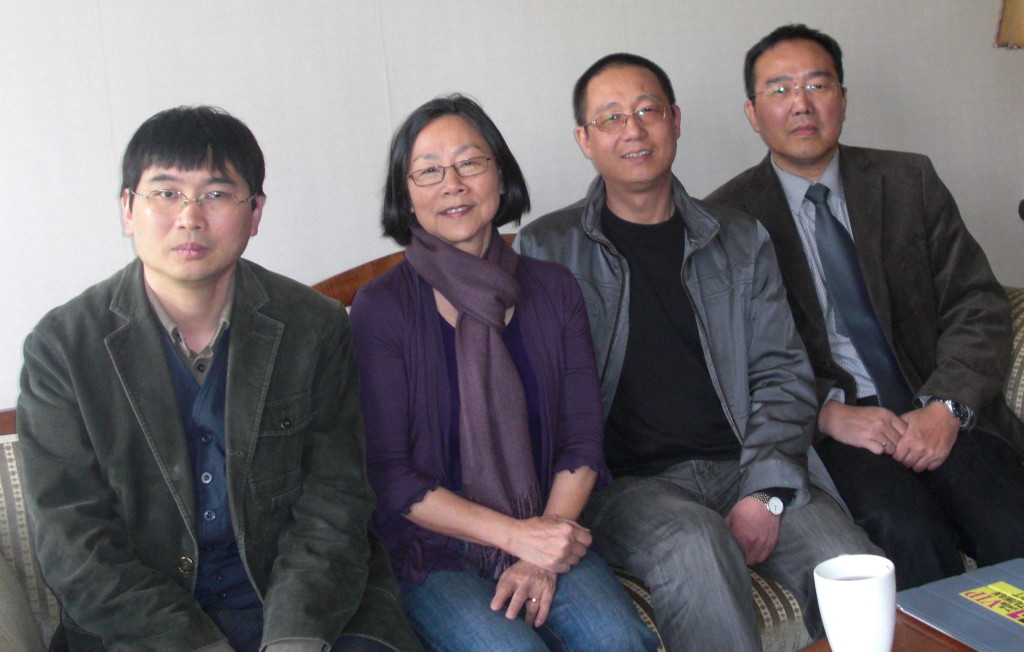

From left to right: Chang Ping, Tienchi Martin-Liao, writer Ye Fu, and a friend, in Amsterdam in 2012. Image courtesy of the author.

China stretches out its hand to control the international media over the authorities’ abduction of a journalist’s family.

Since March 27, the “sibling-abduction” story of the German-based Chinese journalist Chang Ping has been spreading like wild fire. When I got the call from Chang Ping to tell me his three siblings had been detained in connection to an online letter denouncing President Xi’s regime, he had already informed the media. Within hours the international media also reported the news. The Chinese community in Germany immediately published a statement to condemn this barbaric government act. Chang Ping is a close friend. I always like reading his sharp, critical yet gracefully written commentary in the Deutsche Welle. The “abduction” sequence is dramatic and deeply sad. He said: “They take my family as hostage to force me to make deal with them…they send people to my parents’ house daily, to threaten and intimidate them. They tell my family to persuade me to give up my writing as journalist.” Yet Chang Ping refused to make any deal with the police. In his published statement he explained that his siblings have no idea what his thoughts and writings are about. He even wants to break off all relationships with his family so that they will not be blamed for his journalistic practices.

“Kin liability” is an old fashioned practice from Imperial China. If a servant offended the ruler, his whole clan would be punished. There are famous cases of literary inquisitions during the Qin dynasty, like the Zhuang Tinglong Case in 1663 where around 70 people were executed.

The modern Chinese rulers, Tschiang Kai-shek and Mao Zedong, had a complex feeling of respect, fear and hatred for the intellectuals. They did not trust these people and were afraid of the power of words, so they tightened their grip on the intellectuals who held their pens in hand. Xi Jinping does the same. There is a power struggle within the Party, from high officers to cadres of the lower level. Many are against Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption policy. It rips them off all their profitable businesses. Xi’s “reform” in the army also touched the nerves of the military authorities. The country’s economy has slowed down and the smoke is getting thicker. Internationally there is a crevice between China and the US-Japan bond in the South China Sea dispute.

Western politicians, like German president Joachim Gauck, sang the “noisy” democratic hymn in China’s realm, meeting with the untamed artists and lawyers under Xi’s nose in Beijing. The glittering emerald around Xi is fading, the glamor is gone. He needed to refresh his image as a strong man.

Then an opportunity happened: the disobedient journalist Chang Ping wrote “unfriendly” articles published in his column by Deutsche Welle, criticizing the disappearance of writer Jia Jia, who was suspected of being involved in posting the open letter calling for Xi’s resignation. The letter was posted on the government-controlled website Wujie in early March. Chang Ping also gave an interview with Radio France International on the same topic. Far away, in the Sichuan province’s Xichuan Township, the police became active. They rushed to the birthday party of Chang Ping’s father, and without showing any authorized papers, arrested his two younger brothers and sister in front of the stunned guests. The police wanted to press Chang Ping to take down the article. Otherwise, they said, they would punish his siblings with a heavy fine because they committed arson during their worship to the ancestors.

In the past days, the police have released Chang Ping’s siblings. They forced his father and brother to give interviews in China, and blaming Chang Ping publicly. The police also published a letter which appeared to be written by Chang Ping’s brother, Zhang Wei, in which he denied that he was kidnapped by police and regretted that his act of worship had caused a fire on the mountain. He also asked his brother in Germany not to write any anti-government articles. Chang Ping stayed steady. “It’s horse trading. I do not want to join their play,” he wrote to me in an email. He broke all connection with his family in China and hoped that his parents and siblings would understand his attitude. This is the only way to stop the police from doing further harm to both sides.

In a case paralleling that of Chang Ping’s, Wen Yunchao (alias Bei Feng), a prolific exiled writer based in New York, has also learned that his parents and brother also disappeared in their hometown in Jiexi county, Guangdong province, on March 22. The Chinese authorities accused Wen of disseminating a letter asking Xi to resign. Wen was told to hand out the name of his contact person, the letter’s real writer.

Since the kidnapping and disappearance of the Hong Kong publishers Gui Minhai, Li Bo, and their three coworkers, this has been the repeated action of Xi government: stretching hands across the border to silence people and deprive them of their freedom of expression. How far will Xi go? Only the international media reacts and reports on the incidents. Western politicians are quiet, seeming to follow the Chinese government’s official advice: “Do not interfere with China’s internal affairs.” After all, China is not Syria—it does not produce millions of refugees. In the eyes of the international community, sacrificing a handful of people is better than driving tens of millions of Chinese out of the country and creating a “yellow peril.” World politicians understand this simple math well.

Source: http://www.sampsoniaway.org/fearless-ink/2016/04/13/horsetrading-with-abduction/