Xie Yang, Chen Jiangang and Liu Zhengqing, January 19, 2017

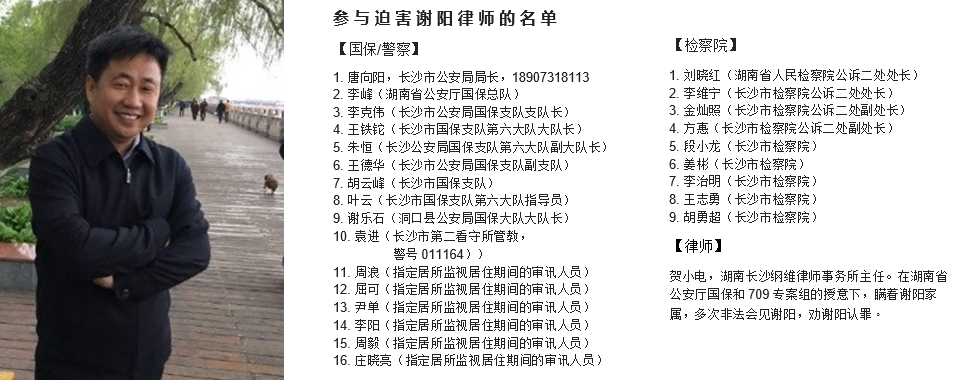

In a series of interviews, the still incarcerated human rights lawyer Xie Yang provided a detailed account of his arrest, interrogations, and the horrific abuses he suffered at the hands of police and prosecutors, to his two defense lawyers Chen Jiangang (陈建刚) and Liu Zhengqing (刘正清). This revelation, and the extraordinary circumstances of it, mark an important turn in the 709 crackdown on human rights lawyers. This group, seen as the gravest threat to regime security, has not been crushed, but instead has become more courageous and more determined. This is the first of several installments in English translation. — The Editors

Date: January 4, 2017, 3:08:56 p.m. (interview start)

Date: January 4, 2017, 3:08:56 p.m. (interview start)

Location: Interview Room 2W, Changsha Number Two Detention Center

Interviewee: Xie Yang (谢阳, “Xie”)

Interviewers: Lawyers Chen Jiangang (陈建刚) and Liu Zhengqing (刘正清) (“Lawyers”)

Transcription by Chen Jian’gang

Lawyers: Hello, Xie Yang. We are Chen Jian’gang and Liu Zhengqing, defense lawyers hired by your wife, Chen Guiqiu (陈桂秋). Do you agree to these arrangements?

XIE: Yes, I agree to appoint you as my defense counsel.

LAWYERS: Today, we need to ask you some questions regarding the case. Could you please take your time and describe the circumstances of your detention and interrogation?

XIE: I was picked up in the early morning hours of July 11, 2015, at the Qianzhou Hotel in Hongjiang City, Hunan (湖南怀化洪江市托口镇黔洲大酒店). As I was sleeping, a bunch of people—some in plain clothes and others in police uniform—forced their way into my room. They didn’t display any identification but showed me an official summons for questioning before taking me away to the Hongjiang City Public Security Bureau. Everything I had with me, including my mobile phone, computer, identification card, lawyer’s license, wallet, bank cards, and briefcase were confiscated. When they got me downstairs, I saw there were three cars waiting. They sent around a dozen or so people to detain me.

LAWYERS: What happened next after you got to the Hongjiang City Public Security Bureau?

XIE: It was around 6 a.m. when we arrived at the station, at the crack of dawn. Someone took me to a room in the investigations unit and had me sit in an interrogation chair—the so-called “iron chair.” Once I sat down, they locked me into the shackles on the chair. From that point, I was shackled in whether or not they were questioning me.

LAWYERS: Did anyone at the time say that you had been placed under detention or arrest? Why did they immediately shackle you?

XIE: No, no one said anything about placing me under any of the statutory coercive measures. They just shackled me right away, and that’s how I stayed for over three hours. No one cared—they just left me shackled like that.

LAWYERS: What happened next?

XIE: Sometime after 9 a.m., two police officers came in. Neither of them showed me any paperwork or identification, either. I could tell by their accents that they weren’t local police from Hongjiang. They hadn’t been among the group that detained me, so they must have come later.

LAWYERS: What questions did they ask you?

XIE: They asked me whether I’d joined “that illegal organization the ‘Human Rights LAWYERS Group’” (人权律师团) and some other questions about the Human Rights Lawyers Group. I said that as far as I knew there was no organization called the “Human Rights Lawyers Group.” They said there was a chat group on WeChat, and I said I was a member of that group. They said: “The lawyers in that group are anti-Party and anti-socialist in nature.” Then they asked questions about who organized the group, what sort of things it did, and so on.

LAWYERS: How did you answer them?

XIE: I said that almost all the members of this group were lawyers and that it was a group set up by people with a common interest. I said it was a place for us to exchange information and that there was no organizer—everyone was independent and equal and there was no hierarchy of any kind. It was only a group for exchanging information and chatting amongst each other, sometimes even cracking jokes and things like that.

LAWYERS: What then?

XIE: Then, one of the officers asked whether we’d publicly issued any joint statements or opinions regarding certain cases in the name of the “Human Rights Lawyers Group.” I said that we had and that this was an act we took as individuals and that we signed as individuals, voluntarily.

Then they asked whether I was willing to quit the Human Rights Lawyers Group. I said that, first of all, since I hadn’t joined any organization called “Human Rights Lawyers Group,” there was no way I could leave it. Then they asked whether I’d be willing to quit the “Human Rights Lawyers Group” chat group. I said that I had the freedom to be part of the chat group and that they had no right to interfere.

LAWYERS: What happened after that?

XIE: They told me the Ministry of Public Security had passed judgment on the chat group known as the “Human Rights Lawyers Group,” saying that there were anti-Party, anti-socialist lawyers in the group. They said they hoped that I could see the situation clearly and that I’d be treated leniently if I cooperated with them. This lasted for more than an hour. They finally said: “Leaders in Beijing and the province are all involved in this case. If you quit the Human Rights Lawyers Group, you’ll be treated leniently.” I asked what they meant by “leniently.” They said I should know that lawyers from the group were being questioned throughout the country and said that there was a possibility that I’d be prosecuted if I continued to refuse to come to my senses.

LAWYERS: What then?

XIE: At the time I thought they’d only brought me in for a talking-to and to see whether I’d agree to quit the group. But I continued to say that the group was only a chat group. They made me give a statement to sign, two pages long, regarding the chat group. The summons said they were investigating “gathering a crowd to disrupt order in a work unit,” but there was no mention of that in the statement. They also asked me about some of the cases I’d been involved in, such as the Jiansanjiang case (建三江案) and the Qing’an shooting case (庆安枪击案). I told them I’d taken part, and they asked me who’d instructed me to do so. I said I went to take part in those cases of my own accord and that no one had instructed me to do anything. What’s more, I said that I’d been formally retained as a lawyer in those cases and that this fell within the scope of ordinary professional work. I’ve since seen my case file, and that statement isn’t in it.

LAWYERS: What happened after you gave your statement?

XIE: After I gave my statement, they said they were relatively satisfied with my attitude and they needed to report to their superiors. They also said that I should be able to receive lenient treatment. Then they left.

About 10 minutes or so later, sometime after 10:30, another police officer came in. He introduced himself as Li Kewei (李克伟) and said he was the ranking officer in charge of my case. I asked him how high a rank, and he drew a circle with his hand and said: “I’m in charge of this entire building.” I guessed he might be the chief or deputy chief of the Changsha Public Security Bureau. I later found out that Li Kewei was the head of the Domestic Security Unit at the Changsha Public Security Bureau.

LAWYERS: What happened then?

XIE: He told me he was not dissatisfied with my attitude. He said I’d only touched very lightly on my own actions and hadn’t “reflected” on things “deep enough in my heart.” He said: “You have to give a new statement, otherwise you won’t get any lenient treatment from us.”

I told him that I was disappointed in the way they were going back on their word. I asked what sort of “reflection” would qualify as “deep enough in my heart”—what was his standard?

He said: “We’re in charge of setting the standard.” I said that if they were in charge of the standard, then there was no way for me to assess it. I told him I was extremely disappointed by their lack of sincerity and that I was unwilling to cooperate with them.

LAWYERS: What happened next?

XIE: Another officer brought in my mobile phone and demanded that I enter the PIN so that they could access my phone. I told them they had no right to do that and I refused. I later found out that this officer was from the Huaihua Domestic Security Unit. He’s someone in charge of my case, but I don’t know his name.

LAWYERS: Then what happened?

XIE: Li Kewei said they weren’t after me and that he hoped I would change my attitude and cooperate with them. Then it was lunchtime. After lunch, there was no more discussion until 5 or 6 p.m. The police had an auxiliary officer stay with me. He didn’t let me sleep at night and kept me shackled like that up until daybreak. For the whole night, the auxiliary officer kept a close eye on me and didn’t let me sleep. As soon as I closed my eyes or nodded off, they would push me, slap me, or reprimand me. I was forced to keep my eyes open until dawn.

LAWYERS: What happened at dawn?

XIE: It must have been after five in the morning when five or six men burst in. Some were in plain clothes and some in uniform. They brought a faxed copy of a Decision on Residential Surveillance and had me sign it. After I signed, they brought me to a police car and took me away.

They drove me all the way to Changsha to a building that housed retired cadres from the National University of Defense Technology (国防科技大学). It was at 732 Deya Road in Kaifu District (开福区德雅路732号) — I saw this in my case file. I had no idea what sort of place it was when they brought me in. I only knew it was in Changsha, but I didn’t know where exactly.

In the car there was a police officer named Li Feng (李峰). I later learned he was from the Domestic Security Unit of the Hunan Provincial Public Security Bureau. He told me I’d already squandered one opportunity and said he hoped I would seize the next one and actively cooperate with them during my period of residential surveillance in a designated location. He said if I did, he’d report up to his superiors and seek lenient treatment for me. I thought that everything I’d done had been above board and I didn’t need to hide anything. I told them the PIN on my mobile phone and he was looking through my WeChat messages the whole ride over. He became very familiar with all that I’d done.

LAWYERS: What then?

XIE: It was about noon on July 12, 2015, when we got to the place in Changsha where they held me. They took me to that hotel and we entered through a side door. There were two police officers on either side of me, each grabbing hold of my arms and pressing on my neck to push me forward. They took me to a room on the second floor, which I later learned was Room 207. It was a relatively small room, with a small bed, two tables, and two chairs. There was a camera in the upper left corner as you entered the room.

LAWYERS: What happened after you went in?

XIE: After they brought me in, they had me sit on the chair. Three people stayed with me. None of them were police. I found out later that they were “chaperones” (陪护人员).

(The interview concluded at 4:54:45 p.m. on January 4, 2017.)

Chinese original 《会见谢阳笔录》. Translated by China Change.

Source: https://chinachange.org/2017/01/19/transcript-of-interviews-with-lawyer-xie-yang-1/