By ANJAN SUNDARAMJULY 25, 2014

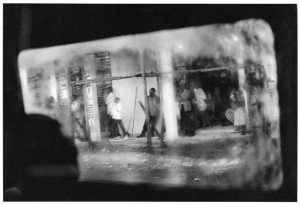

The Democratic Republic of Congo, 2002. Two wars since 1996 have killed more than five million people. Credit Paolo Pellegrin/Magnum Photos

LISBON — THE Western news media are in crisis and are turning their back on the world. We hardly ever notice. Where correspondents were once assigned to a place for years or months, reporters now handle 20 countries each. Bureaus are in hub cities, far from many of the countries they cover. And journalists are often lodged in expensive bungalows or five-star hotels. As the news has receded, so have our minds.

To the consumer, the news can seem authoritative. But the 24-hour news cycles we watch rarely give us the stories essential to understanding the major events of our time. The news machine, confused about its mandate, has faltered. Big stories are often missed. Huge swaths of the world are forgotten or shrouded in myth. The news both creates these myths and dispels them, in a pretense of providing us with truth.

I worked in the Democratic Republic of Congo as a stringer, a freelance journalist paid by the word, for a year and a half, in 2005-06. There, on the bottom rung of the news ladder, I grasped the role of the imaginary in the production of world news. Congo is the scene of one of the greatest man-made disasters of our lifetimes. Two successive wars have killed more than five million people since 1996.

Yet this great event in human history has produced no sustained reporting. No journalist is stationed consistently on the front lines of the war telling us its stories. As a student in America, where I was considering a Ph.D. in mathematics and a job in finance, I would read 200-word stories buried in the back pages of newspapers. With so few words, speaking of events so large, there was a powerful sense of dissonance. I traveled to Congo, at age 22, on a one-way ticket, without a job or any promise of publication, with only a little money in my pocket and a conviction that what I would witness should be news.