Madeleine Thien Photo: Babak Salari

In Ms. Thien’s novel, multiple generations are linked by an at-times taboo love for Western music

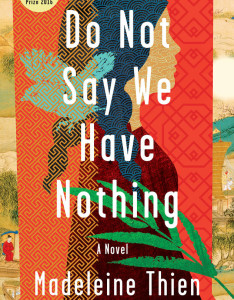

Even during the chaos of the Cultural Revolution, China maintained a symphony orchestra at the behest of Mao’s wife. It’s one of the surprising artifacts of history unearthed in Madeleine Thien’s latest novel, “Do Not Say We Have Nothing,” a rich, sprawling tale centered on tragedies that unfold at the Shanghai Conservatory of Music amid the brutal struggles of that era.

In Ms. Thien’s novel, multiple generations are linked by an at-times taboo love for Western music, as well as the manuscript of a novel, the “Book of Records,” broken into fragments carefully hand-copied and hidden away during political turmoil.

Photo: W.W. Norton & Co.

Ms. Thien, a Canadian, traveled for a year in China researching the book, which spans some 60 years, culminating in the Tiananmen Square protests. The book, which was short-listed for the Man Booker Prize, was published in the U.S. last month by W. W. Norton & Co. The Wall Street Journal spoke with Ms. Thien about her travels and research as well as classical music during the Cultural Revolution. Edited excerpts:

The idea of hand-copying texts repeats as a motif in the book. What was the inspiration?

My mother put us in calligraphy classes when I was a kid. Often the teacher would just hold your hand over the brush and your hand would move with his. It was beautiful, this idea you’d just attentively follow lines left by someone else—and in doing so, fall in the rhythm of their breathing. The idea you spend years tracing, learning the ways of those who have come before and then decide upon your own style of calligraphy, it’s astonishing. It’s not really an idea we have in the West, where newness and originality is always a break from the past.

Do you think your book will ever be published in mainland China?

A few publishers have been in touch. They’ve talked about it in different ways–like if we took out the last third [involving Tiananmen], we could publish. But nobody wants to publish it that way. The only person who’s actually open to it is me. It fits in with the book, with the idea that the “Book of Records” exists in fragments, that there’s going to be one record here and another there and that it’s ongoing. I almost wish they’d publish it and let it end mid-sentence.

Your book spans some six decades. What was the hardest era to research?

In a funny way it was the 1980s. There’s a lot on the Cultural Revolution, from memoir to fiction. The 80s was such a fascinating transitional time, and what was hard to find was work that [spoke] to the psychological transition that was happening and the generational shift that was post-Cultural Revolution but pre-Tiananmen.

Were the parts of your book involving He Luting [Shanghai Conservatory president, known for his resistance during the Cultural Revolution] based on history?

Yes, everything with him is historically accurate. He’s one of the few real people in the book. There’s an amazing documentary, From Mao to Mozart: Isaac Stern in China [1979]. It won an Oscar, it was quite beloved at the time. One of the really moving parts is Isaac Stern recognizes right away there’s a huge difference between [musicians] who are 19, 20 or 21 or older who didn’t get to practice all these years during the Cultural Revolution. He says something is missing in their playing, some deeper engagement with the music different from those who are eight or nine or 10 years old—the ones too small to really experience the Cultural Revolution—who seem to be a lot more fearless about the music’s emotions.

What were some of the other materials you found most helpful in your research?

There’s a wonderful book, Woman from Shanghai. You know, in China, there’s an interesting genre of docufiction, interviews with people that’s almost documentary, but also a cross-genre form, composed so when reading it, it feels like you’re reading fiction. It’s an incredibly powerful use of narrative technique.

You mean books like Liao Yiwu’s Corpse Walker?

Yes, exactly. I feel there’s something quite natural to it in Chinese literary canon—this idea of the scholar-poet. The Tang Dynasty poets wrote very personal poems, but were also politically engaged and very highly educated, and many went into exile after critiquing one leader or another. I feel there’s a true line here from the scholar poet all the way to Ai Weiwei, Liao Yiwu and so on. They are poets but also they feel they have a duty to the people—that their role is to stand before power and speak honestly.

What’s the Shanghai Conservatory of Music like today?

It’s in the French Concession, it’s an oasis. I spent a lot of time there wandering around. In the conservatory, there is a very small memorial to the teachers and students who lost their lives in the Cultural Revolution. It has all their portraits. There was a high number of suicides, especially of teaching faculty. It’s a very moving thing, very out of the way, very respectful and discreet.

– Te-Ping Chen. Follow her on Twitter @tepingchen.