A review of Stein Ringen’s ‘The Perfect Dictatorship: China in the 21st Century’

A review of Stein Ringen’s ‘The Perfect Dictatorship: China in the 21st Century’

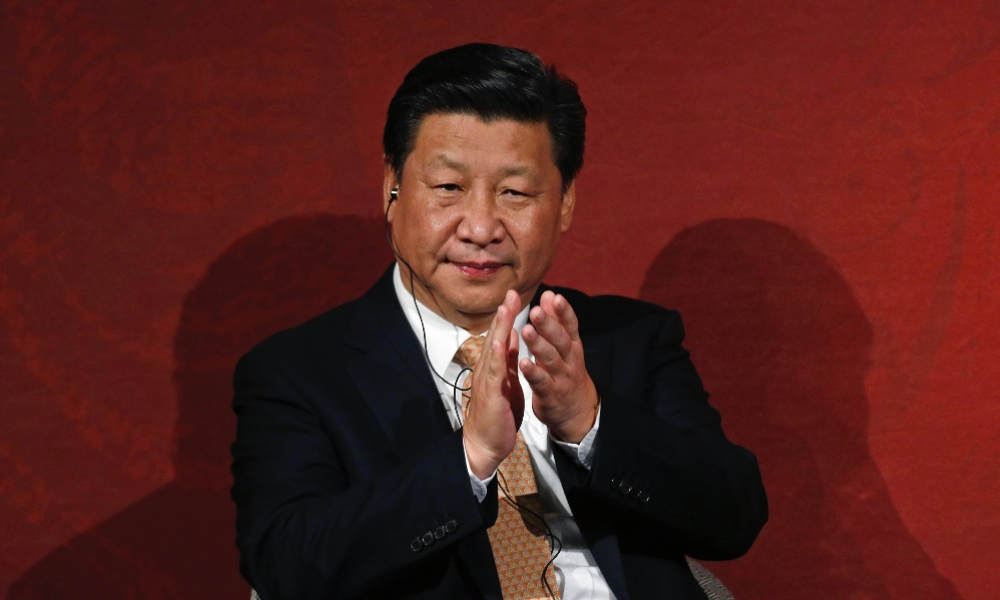

Back in late 2012, when Xi Jinping (習近平) first came to power, there was a flurry of opinion that said he was China’s long-awaited liberal reformer. As time passed, everyone could see that Xi was clearly heading in a more dictatorial rather than democratic direction — purging critics, consolidating power within the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), squeezing civil society, arresting rights lawyers, and in the economic arena, unable to boast of anything little better than a lackluster record on meaningful reform.

The rapidly dwindling ranks of wishful thinkers switched to arguing that he was a closet reformer, that once he had weeded out the hardliners and secured the support base he needed, he would swoop back in with those reforms. Now, four years on, hardly anyone believes in Xi the Reformer. What is amazing, however, is that Xi never said he was a reformer; those who saw him as one were merely projecting their own hopes on the man.

This is something that Norwegian political scientist and emeritus professor at the University of Oxford Stein Ringen could have told us four years ago, and something which he urgently warns us to do now when evaluating the Chinese state today.

In his refreshing new book The Perfect Dictatorship: China in the 21st Century, Ringen argues that too many of us see China through reform-tinted glasses (comrades, it’s time to wake up and smell the ergoutou!). He says that one way to understand China is to listen to what its leaders say and to look at what its leaders do. China never said it would be a liberal democracy and it has never acted like one. So what is it?

The clue is in the book’s title. Ringen describes the Chinese system as “sophisticated totalitarianism”; a Party-state obsessed with control (for which he coins a new word, controlocracy). China has co-opted the middle and working classes and is out for itself and not for the people; welfare policies are just enough to secure legitimacy and stability and do not emerge out of any sense of fairness or justice. CCP survival trumps all, and isn’t that a rather frightening raison d’être for any state? As he dismisses the genuineness of its welfare aspirations, Ringen even likens it to a kleptocracy. The author is unforgiving; The Perfect Dictatorship is a no-holds barred warts-and-all, de-robing of the party-state to its ugliest (from a western liberal point of view) incarnation. Ringen isn’t wearing reform-tinted glasses, if anything, he’s wearing the opposite kind.

The layout of the book is pleasingly simple: Ringen says his aim was to get at a true understanding of China, right down “to the soul of the Chinese state” — and the book has been sectioned into chapters headed: “What they say,” “What they do,” “What they produce” and “Who they are.” He tackles each in turn, using his background as a political scientist with a four-decade focus on state analysis and democracies, pooling facts and interpreting data to answer, or provide the most likely answers as he sees it. He is not a China hand — which gives him the freedom, he says, to reject even a whisper of self-censorship since he’s not beholden to Beijing. He doesn’t need to worry about having his visa denied — a genuine risk for scholars who don’t curb their tongue these days — he has made all his research trips to China already.

Earlier, I called the book refreshing and that is because he does what so few China scholars have done: he has given dignity to the hundreds of millions of migrant workers by giving them due credit as the real backbone behind China’s economic miracle and massive poverty alleviation effort. This is something that China apologists or Sinophiles consistently overlook, solely attributing China’s rapid economic growth and the lifting of 500 million people from poverty as grand CCP achievements. Further, crowing about post-1978 achievements is a bit rich when the Party hasn’t even remotely begun to address the crimes against their own people that were waged decades earlier during the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution.

Part of our love affair with China stems from the fact that we have consistently over-estimated it, he argues (and when we’re in love we’re not rational about the other’s faults). China’s economic miracle is an exaggeration because unreliable official statistics have inflated growth and a good portion of that growth has been “fake” or “empty,” driven by debt and built on bad investments. He notes that China’s own National Development and Reform Commission estimated that half of the investments into the Chinese economy between 2009 and 2013 were “ineffective.” He suggests that the economy is likely only two-thirds of the official size.

Ringen doesn’t even rate China as highly as South Korea as an Asian dragon in the 1980s and 1990s. South Korea developed into a high-income country, it became democratic, and created social protections for its people; China, he says, hasn’t even come close. What turns people’s heads with China, he says, is simply its size. A country with a population of 1.4 billion will make any statistics gasp-worthy. We all know that size matters, but what’s more important is what you do with it and Ringen is not impressed. “China’s achievements are big in quantity but small in quality.”

One thing that might disappoint is the lack of human element in The Perfect Dictatorship — both the part played by the Chinese people and the individuals who make up the top echelons of the Party. Ringen excuses himself from this task by arguing right from the start that he is attempting “a political analysis of the state” not a “sociological one.” It is true that this makes the book a little brittle: there are no anecdotes, human voices or color. It also feels like there is something missing; can you really understand China without at least attempting to evaluate the people at the top and the masses at the bottom? What do they want? But for anyone interested in the country today and what it might turn out to be tomorrow, his writing is thorough and authoritative, his arguments forceful and sharp, and it’s still a page-turner.

By the end of the book, Ringen is sounding a warning bell about China and its global intentions, urging us to see it for what it is and not what we want it to be. He makes a not so subtle comparison with how many admired Nazi Germany and the Soviet Union in their early days. He struggles through a number of scenarios about China’s likely future trajectory — no spoilers here, you will have to read the book — but he does have stern words about the possibility of a new nationalist ideology taking hold. Beware the “China Dream” because it may just turn out to be a nightmare.

The Perfect Dictatorship: China in the 21st Century

The Perfect Dictatorship: China in the 21st Century

Hong Kong University Press, 2016

208 pp

First Editor: J. Michael Cole

Second Editor: Olivia Yang