[image credit: OUP // Leila Navidi]

[image credit: OUP // Leila Navidi]

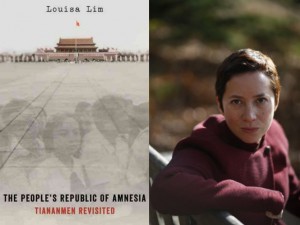

With the 25th anniversary of the violent suppression of student protests on June 4, 1989 coming upon us next week, we spoke to Louisa Lim, a journalist for NPR who has written a book about the events of 1989 and their consequences. The People’s Republic of Amnesia: Tiananmen Revisited comes out on June 4, the day of the anniversary. Lim answered our questions about her book and the anniversary by email.

Your book is coming out on the 25th anniversary of Tiananmen. When did you decide to write a book on this subject and when did you begin your research?

I began writing my book at the beginning of last year, but I had been thinking about it for a much longer time. It struck me that, although there had been a flood of Tiananmen books in the immediate aftermath, almost nothing had been written in recent years about its legacy from inside China. At first I was reluctant to broach such a radioactive topic, but one question kept gnawing at me: if I don’t write this book, who will? Eventually I decided that it was a book that needed to be written.

The last chapter of your book concerns Chengdu, where a bloody riot and subsequent crackdown occurred in the days after June 4. You write that this was a story that was not only forgotten but was never properly told at all. Could a similar story be told of other cities that saw unrest as well?

Yes, there are definitely other untold stories, given that huge protests happened in dozens of cities around China. Apart from Chengdu, the best-known scenes of violence were in Xi’an and Changsha, where mass demonstrations were suppressed on April 22nd. In Xi’an, 40,000 people had gathered in the New City Square to mark the funeral of former party leader Hu Yaobang. When their attempts to present a petition were rebuffed, jostling between police and citizens disintegrated into scuffles and rock-throwing, after which riot police and military police moved in with batons and clubs. Local television aired footage showing police kicking and beating bloodied students inside the government compound. The government claimed that nobody had died, but students said that around a dozen people were killed. Also on April 22nd, a protest in Changsha was violently suppressed. Reports at the time said a student protest had been ‘infiltrated’ by groups of unemployed youth who looted around 40 shops. An academic who had been there, Andrea Worden, wrote, “One popular activity among the ‘youths’ that night had been to commandeer trucks and drive at top speeds up and down May First road singing, ‘The East is Red.’” One person died and many were injured. If official figures can be taken as a guide, neither of these incidents were as bloody as the suppression in Chengdu. It’s likely there was unrest elsewhere which was never reported, but I chose to focus on Chengdu because the violence there had been so very brutal, as well as being relatively well-documented due to the presence of a US consulate.

This leads me to a question on terminology. Is “Tiananmen” the best word to use to represent these events? As you point out, other cities saw similar protests and crackdowns. What is your preferred term?

That’s actually a question that I continue to struggle with. In many ways, the shorthand of Tiananmen is misleading, since – as you point out – it fails to take into account the nationwide nature of the protests, and when it comes to the actual deaths, most were not in the square itself but on the approach roads. I tried using “June 4th”, but that proved unsatisfactory since there were deaths both before and after that date. It also lacks the instant recognition value outside China as “Tiananmen”.

As a side note, I was surprised to find that my own book was classified in the Library of Congress cataloguing system under “Tiananmen Square Incident, 1989”, which is the bland nomenclature favoured by the Chinese government itself. To me, calling the murderous suppression of protests an “incident” is not just an act of omission. It’s an act of mendacity.

Amnesia as a medical phenomenon often occurs after a traumatic event. How much of the amnesia about June 4th do you think is a coping mechanism and how much is it a result of effective propaganda?

Forgetting was perhaps an easier option to deal with the heartbreak that came from having hopes raised so high, then so thoroughly, violently trampled. Some people made a cold-blooded calculation, and decided that the cost of remembering was simply too high. One of the co-founders of the Tiananmen Mothers, Zhang Xianling, described the immediate post-Tiananmen era as a period of ‘White Terror’, but even she was horrified to discover that some parents would rather disown their own dead offspring than admit they had been killed that night, due to the stigma of being associated with the ‘counter-revolutionary riots’.

It’s important to remember that effective propaganda is also being bolstered by the use of punitive measures, which serve as a clear warning to anyone who might try to publicly remember June 4th. This year, the repression is being stepped up, and even private acts of remembrance inside people’s homes are being punished, as seen by the detention of five activists, lawyers and dissidents who attended a “June 4th commemoration seminar” in Beijing. The soldier-turned-artist Chen Guang, who staged a work of performance art for a handful of friends, is also in detention. So far, a total of eleven people have already been detained in the pre-anniversary roundup, which really underlines how fearful the state is of those who challenge its historical narrative.

I was fascinated by the tensions between the Tiananmen Mothers and Liu Xiaobo. Other leaders of the movement have been criticized too and accused of being self-aggrandizing. Do you think that the type of personality it takes to be a dissident and a leader of a protest movement attracts people who are uncompromising and therefore perhaps difficult to get along with?

There is definitely a personality type, since being a dissident or the leader of a protest movement requires a tremendous amount of determination, persistence and self-belief, though I don’t think being a difficult personality is a given. In fact, a large dollop of charisma is generally required to win others over to the cause. On this, perhaps the last word should go to the exiled student leader, Wu’er Kaixi, who was number 2 on the Most Wanted list issued by the Chinese government after 1989. We were talking about this very issue, and he said to me, “I have met with many dissident leaders around the world. We are all more or less zilian [ed: narcissism]. It’s kind of required – to be self-involved – to be a martyr.”

Follow Louisa Lim on Twitter at @LimLouisa. The People’s Republic of Amnesia: Tiananmen Revisited is available for pre-order now in hardback and ebook.

From http://shanghaiist.com/2014/05/26/interview_louisa_lim.php