–Author’s Preface

In Chinese dictionaries published since the founding of the People’s Republic of China (PRC) in 1949, the definition of Literary Inquisition is restricted to “the rulers of olden times”; at the very least, it is a relic of the past, occurring no more recently than a century ago, mainly during the Ming and Qing dynasties. In the Mandarin Dictionary published by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of China (ROC, Taiwan), Literary Inquisition is defined as occurring in the “era of absolute monarchy”, precluding its existence in the Republic era. A revised edition has amended the definition to read, “During the autocratic era, criminal cases arising from the written word”. This last definition is the common usage adopted by contemporary Chinese literature, and also for this book.

The etymology of the Chinese term for Literary Inquisition (Wenzi Yu) derives from a verse by the Qing dynasty poet Gong Zizhen, who in his poem “Ode to History” described literati who wrote only for enjoyment while carefully avoiding any word that might bring them punishment as living under Literary Inquisition. According to the above definition, however, the earliest record of literary inquisition goes back over 2,000 years to the Western Han dynasty. According to the History of the Han (Hanshu), Yang Yun, a grandson of the great historian Sima Qian, was demoted, and during a search of his home in 45 B.C., a draft letter he wrote to a friend, Sun Huizong, complaining about his situation was found. Although the letter praised the Emperor Xuanzong, the emperor regarded the letter as treasonous and ordered Yang Yun cut in half. Sun Huizong and a number of other acquaintances were also implicated and dismissed from office.

Su Shi (Su Dongpo), a statesman and scholar in Northern Song, is the most famous victim of literary inquisition. In 1079, during the reign of Emperor Shenzong, while Su Shi was transferred to be a prefect of Huzhou, imperial censors accused him of complaining in his letter of thanks to the emperor, and of malign and slanderous content in some of his poetry as well. He was arrested and imprisoned for nearly five months, facing execution, but thanks to the intervention of the Empress Dowager and current and former prime ministers, he was merely demoted and banished. Implicated with him were the celebrated literary scholar Sima Guang and more than 20 other officials of various ranks.

Literary inquisition became worse with each dynasty and era, and was especially prevalent during the Qing dynasty, when a few isolated words and phrases quoted out of context could bring a death sentence. The “case of Zhuang Tinglong’s Ming History,” occurring just before Emperor Kangxi came to power, implicated the largest number of people and was dealt with most harshly. The merchant Zhuang had commissioned the production of a History of the Ming Dynasty, which did not follow the official term of “puppet Ming” (Wei Ming) when referring the defeated inheritors of the previous Ming dynasty. More than two thousand people were implicated, including Zhuang’s father, who had printed the book in memory of his son. Seventy-two were executed (eighteen by dismemberment), and more than seven hundred were sent into exile. The so-called flourishing age of the Emperor Qianlong period had more than one hundred and thirty cases of literary inquisition in sixty-four years.

Since the Republic of China was established in 1912, restrictions on expression were relaxed, but literary inquisition still occurred on occasion. While the Beiyang Government in Beijing dominated northern China until 1928, the Fengtian warlord Zhang Zuolin imposed brutal despotism over his subjects for a four-year period in the 1920s that included the execution in broad daylight of independent newspapermen Shao Piaoping and Lin Baishui.

The national government in Nanjing imposed autocracy in the name of “political tutelage”, strengthening prohibitions on expression from 1927 onward, mainly through censorship of printed works. Although books were banned and texts excised, harsh punishment was rare; still, Chen Duxiu, the founding General Secretary of the Communist Party of China (CPC) who was imprisoned by the Kuomintang (KMT, Chinese Nationalist Party) in 1932, wrote in a satirical poem: “Thanks to be the magnanimity of the party-state, which bans books rather than burns them. Literary inquisition still thrives in the Republic, alas!” Two cases of literary inquisition drew the greatest public approbation at this time: In Shanghai, the chief editor of Rebirth Weekly, Du Chongyuan (Tu Chung-yuan), spent more than a year in prison after an article drew severe protest from the Japanese government for “insulting the Emperor and damaging diplomatic relations”. In the second case, the editor-in-chief of Jiangsheng Daily, Liu Yusheng, revealed that General Gu Zhutong (Ku Chu-tung), the governor of Jiangsu Province, and other senior officials had auctioned off opium seized during drug raids, among other corrupt acts. In retaliation, Ku claimed that short stories published in one of the newspaper’s supplements “promoted communism” and “instigated class struggle”, and without going through the process of trial, Liu was summarily executed for “endangering the Republic”.

The harshness of the modern Communist regime has far exceeded that of all past despots, as the PRC’s founder Mao Zedong openly acknowledged: “What was Emperor Qin Shi Huang? He only buried 460 scholars, but we buried 46,000. During the suppression of counter-revolutionaries, didn’t we kill some counterrevolutionary intellectuals? I’ve discussed this with pro-democracy advocates: ‘You call us Qin Shi Huang as an insult, but we’ve surpassed Qin Shi Huang a hundred-fold.’ Some people curse us as dictators like Qin Shi Huang. We must categorically accept this as factually accurate. Unfortunately, you haven’t said enough and leave it to us to say the rest”.

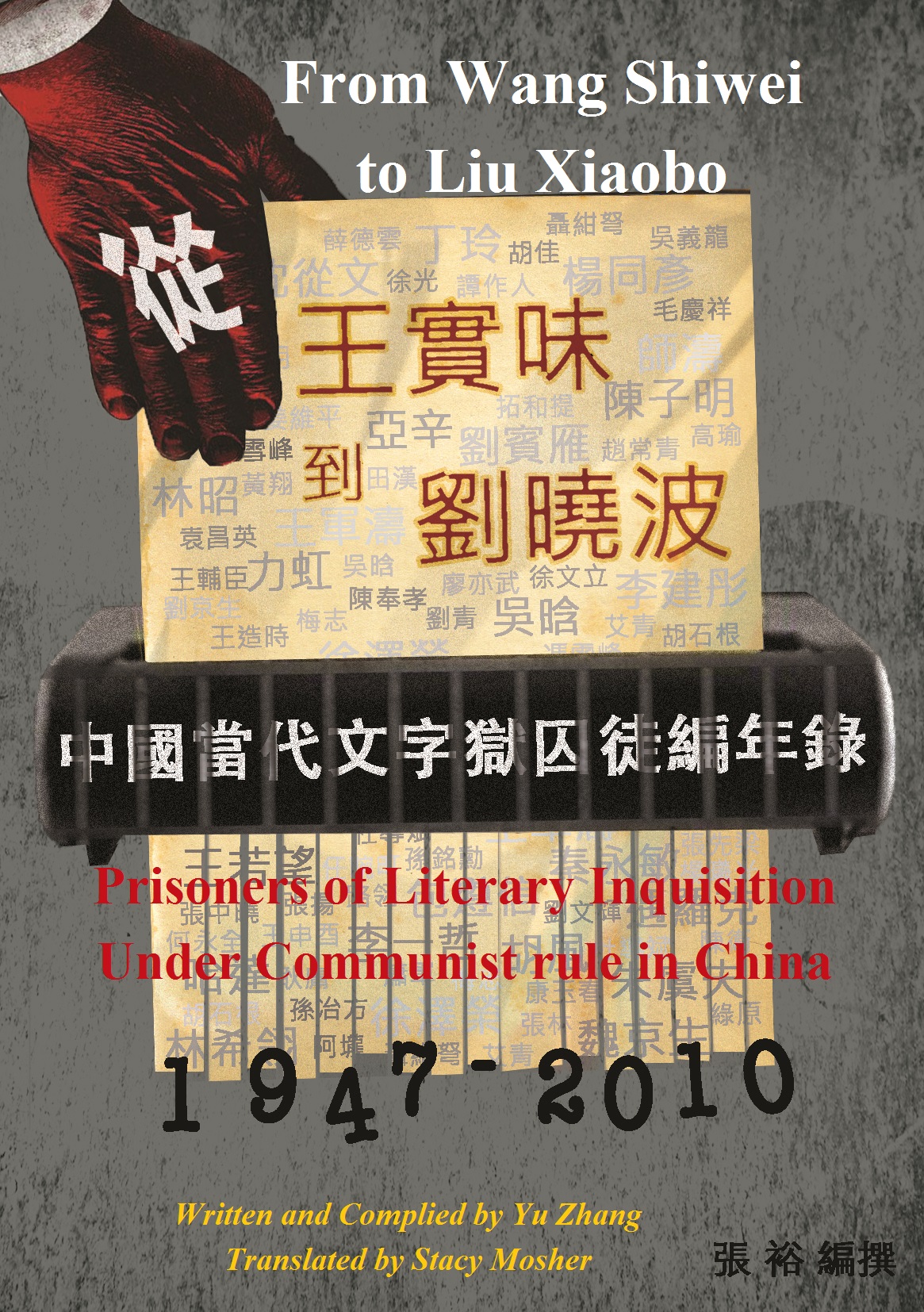

In fact, the number of writers killed under CPC rule far exceeds 46,000, and the number imprisoned is incalculable. This volume collects 64 cases occurring from 1947 to 2010, with one emblematic case for each year, but these represent just the tip of the iceberg. The CPC has officially acknowledged that 550,000 people were labeled “Rightists” from 1957 to 1959, mostly through various types of literary inquisition, making the 130-plus cases of the Qianlong period pale in comparison. This volume describes the cases of 12 “Rightist” victims – Sun Mingxun, Feng Xuefeng, Lin Xiling, Ding Ling, Ai Qing, Lin Zhao, Wang Ruowang, Wang Zaoshi, Chen Fengxiao, Yuan Changying, Nie Gannu and Liu Binyan, obviously only a minute proportion. In the single case of the “anti-Party” novel Liu Zhidan, more than 10,000 people were persecuted, the most wide-ranging literary inquisition in Chinese history. In the case of Wang Shenyou’s love letter, Wang ripped up the letter before sending it, but he was forced to rewrite it and was then executed for his “unspoken criticism”. A multitude of such cases demonstrates that literary inquisition has reached its fullest flowering under CPC rule.

Marking its 50th anniversary in 2010, the Writers in Prison Committee (WiPC) of PEN International (previously International PEN) issued a list of 50 cases of writers imprisoned all over the world during the past 50 years. The Independent Chinese PEN Center (ICPC) responded by compiling 50 cases involving 58 Chinese writers. This volume has revised and supplemented the original list to provide the biographies of 71 victims in 64 cases.

This volume highlights the most representative cases involving the most influential people persecuted during various political movments and campaigns under CPC rule. For this reason, even though the Yan’an Rectification Movement occurred prior to the establishment of the PRC, it is the first large-scale literary inquisition known to have taken place in a CPC-ruled territory, and so its most famous victim, Wang Shiwei, has been selected as the first case in this volume. However, because other writers who came under criticism with Wang at the time, such as Xiao Jun, Ding Ling and Ai Qing, underwent literary inquisition during subsequent political movements, and the experiences and case details of other victims of the same period remain unclear, no other cases have as yet been identified during the period from when Wang was imprisoned in 1942 until his execution in 1947; for that reason, the year of Wang’s execution has been made the starting point of this volume, even though his case began five years earlier.

Some large-scale literary inquisitions, such as the case of the “Hu Feng Counterrevolutionary Clique” and the Anti-Rightist Campaign, had a large number of victims, or their most prominent cases all occurred in a single year. Apart from the primary or most influential victims of these campaigns, some additional victims are allocated to years in which they first came under criticism or were arrested, tried, sent to labor reform, imprisoned, executed or released. The cases of Ah Long, Lu Ling, Geng Yong, Zhang Zhongxiao, Mei Zhi and Lü Yuan, all persecuted as “core members of the Hu Feng Clique”, are recorded in this way.

In addition, some political mass criticism campaigns targeting cultural works such as the film The Life of Wu Xun and Yu Pingbo’s research on The Dream of the Red Chamber did not result in the actual writers, editors or publishers of these works being victimized; as a result, the individuals included here are others implicated in those cases, such as Sun Mingxun and Feng Xuefeng. In fact, however, few of those involved escaped the Cultural Revolution that followed a decade later.

In addition, the case of Shen Congwen is not one of literary inquisition in the narrow sense; he was not denounced or imprisoned by the authorities because of his writings, but rather was criticized just as the CPC was about to take power. In this respect, he can be considered a spiritual prisoner of literary inquisition, and is therefore included as a special case.

Since ancient times, victims of literary inquisition have always included idealists who have intentionally violated literary taboos, but there have also been many who have fallen victim by unintentionally offending the authorities. Using the pen name Du Deji, Lu Xun wrote in the essay “Barriers”: “I had always thought that literary disaster resulted from taunting the Qing rulers. Yet, in fact that was hardly so… Some were crude and rash, some were crazy, some were rustic pedants unconscious of taboos, some were of the ignorant masses genuinely concerned about the imperial royalty… who actually regarded His Majesty as their father and lovingly toadied to him like a pampered child. Why would he want such a servile person as his child? Therefore he must be put to death”. Lu Xun was satirically gloating over the suppression of Shen Congwen and other independent writers, but this is still an accurate summation. The famous victims of literary inquisition recorded in this volume include many who acted in good faith. At least ten were originally loyal and steadfast members of CPC and more than half were pro-Communist, many remaining so until their dying days. Wu Han is a classic example; the literary work for which he was persecuted was “written to order”. It is just such cases that expose the absurd, anti-intellectual and anti-civilized nature of literary inquisition. However, the biographical sketches included in this volume are to the greatest extent possible devoid of comment, and make no judgments or categorizations based on politics, morality or literary quality.

These brief biographies of the victims of literary inquisition have whenever possible been vetted by descendants, friends or family members, to whom the author and compiler here expresses special thanks. Some of the case data was collected and sorted out by Miss Li Jianhong, the coordinator of ICPC-WiPC, and I thank her and other ICPC colleagues who contributed revisions and suggestions.

Translated by Stacy Mosher