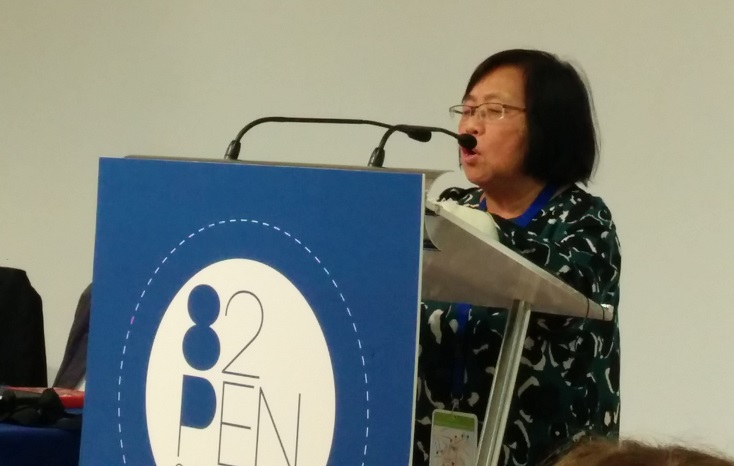

Wing Mui TSOI speaking at PEN International 82nd Congress held in Ourense, Spain, on 28 September, 2016

There once was a famous saying in Hong Kong: A border separates Hong Kong from Mainland China. On both sides of this border are the same people with the same cultural tradition and they belong to same race. But there is a key difference: People on one side can criticize anyone but their government while people on the other side can criticize anyone but their wives.

This other side is Hong Kong.

In 1997, Hong Kong was returned to People’s Republic of China. Although China has been one of the worst speech censorship offenders – Facebook, Twitter, Youtube , google are banned in China (and netizens has to “Fan Qiang”— bypass the internet firewall to use it) – Hong Kong has continued to enjoy its freedom of expression, in accordance with the One-Country-Two-Systems Principle agreed upon between China and the Great Britain in 1984. In fact, even after 1997, Hong Kong once was the freest place for publishing among all Chinese communities around the world. You could publish any sensitive books there, even those that were strongly critical of Beijing. This press freedom in post-1997 Hong Kong has cracked open a window for some curious Mainland Chinese to peep into any and all sensitive political issues banned at home. The interest was so great that publishing books on politically sensitive topics became a booming business in Hong Kong.

Sadly, that is no longer the case.

On a rainy day in March this year I brought a Swedish reporter to visit 5 bookstores in a busy downtown area in Hong Kong called Causeway Bay. These 5 bookstores can be divided into three kinds.

The first kind is the Eslite Bookstore, the largest retail bookstore chain from Taiwan and occupies 3 enormous floors in a modern building . We looked around for a long time but could not find any politically sensitive books. It was clear that the giant chain chooses not to stock anything politically sensitive because it has an ongoing business relationship with China. In fact, it just opened up its first branch in Mainland China. Eslite clearly has an incentive to not offend Beijing.

The second kind is also a big bookstore: the Chinese state enterprise Commercial Press. Unsurprisingly, in this huge 4-floor bookstore, we couldn’t find any books containing any sensitive issues. Instead, we saw a lot of Chinese official propaganda though.

The last 3 bookstores fall into the third categories. They are small independent stores each with a size of no more than 1000 square feet. Locals call them second-floor bookstores because they are usually on the second or third floor of some rather old walkups, as they simply cannot afford to pay expensive rent. These independent bookstores are the only ones that stock any books that are censored by the rest of the publishing world. One of them is the now well-known Causeway Bay Bookstore. When we got there it was permanently closed. Another one closed its business not long after our visit. Now, only one such independent bookstore one exists, which means you can only buy banned books in a very small bookstore in the whole downtown area.

And that is only the retail side of the story. The printing, publishing and wholesaling of politically sensitive books also face huge difficulties. After the month-long protest known as the Umbrella Revolution in 2014, all books about the revolution were returned to the publishing houses and then sent to be recycled. This is because wholesalers were pressured to not send them to retail stores.

How did this censorship happen? When did it begin? Well, Hong Kong’s publishing community clammed up after two things happened.

First, in 2015, a publisher named Yiu Mantin was sentence to 10 years in prison in China, officially for the crime of smuggling . But it is widely known that he was imprisoned for his plan to publish a book by a U.S.-based dissident writer. The book is called “Chinese Godfather Xi Jinping.” Xi Jinping simply cannot tolerate being compared to the Mafia. The second is the Causeway Bay Bookstore Incident where 3 booksellers were arrested in Mainland China and 2 more kidnapped in Thailand and Hong Kong and then smuggled into China.

These are the two cases our Independent Chinese PEN Center (ICPC) and PEN International put on the list of concerned cases.

First, let’s talk about the imprisoned publisher Yiu. Yiu is a real hero who sacrificed himself for the freedom of press. Unlike many other booksellers, he did what he did not for profit, but to give a voice to the voiceless. Most of the books he helped publish, including 21 books for ICPC’s members, actually cost him money. His case is 100% political persecution and 100% suppression of press freedom. In fact, it was Yiu’s case that first sent chills down the spine of Hong Kong’s publishing community. The book “Chinese Godfather Xi Jinping” could not find another publisher after Yiu was sentenced. Eventually, the Open Publishing House, where I used to work, decided to take over its publication. But its publisher Jin Zhong, my old boss, was so scared that he had to watch over his shoulder whenever he left his house. Unfortunately, Yiu’s case has not received its due concerns from public opinion and human rights organizations.

Then there was the more serious case of Causeway Bay Bookstore Incident. Chinese secret agents crossed the border to kidnap Lee Bo of Causeway Bay Bookstore and smuggled him into Mainland China. Under duress, Lee said publically he committed the crime. The incident really scared ordinary Hong Kong people and destroyed Hong Kong’s publication freedom. Immediately after the news broke about Lee Bo’s kidnapping, Page One, a famous Singapore bookstore chain and publisher, removed all sensitive books from their store at Hong Kong’s airport and announced that it would not restock these titles in Hong Kong once existing stock has been exhausted.

Some printing houses also self-discipline to avoid printing what they consider sensitive publications. Worse still, most Mainland Chinese no longer dare to buy these books to bring back home because Chinese customs has increasesd its crackdown on political sensitive publications.

The profit of Mirror Publishing House, which focuses on political books, recently decreased by 70%. One by one, political magazines, such as Open Magazine where I had worked for 20 years, had to cease publication.

Hong Kong’s publishing industry is now in its winter.

I will give you a very personal example.

The day before the news of Lee Bo’s kidnapping broke, my book “The Secret Emotional Life of Zhou Enlai” was published. It immediately became one of the banned books upon publication for 2 reasons.

First, my book focuses on Zhou Enlai, who was China’s premier during Mao Zedong’s era. He was the second most important figure, just after Mao. He was and still is regarded as a saint and a caring father-figure to the Chinese people. In China, the tone of political commentaries about high ranking leaders like

Zhou is officially set by the government. Any challenge to the official determinations automatically leads to censorship. Second, my book suggests that

Zhou was a closeted homosexual. Because the topic of homosexuality is still a taboo in Mainland China, my book becomes even more controversial in the eyes of the Beijing government. It would be considered a blasphemy against a saintly revolutionary leader.

A month after my book was published, my Facebook account was suddenly blocked and I was required to verify my account with proper identifications or I would lose all my 9 years of Facebook content. I was shocked. I was angry and I did not know what went wrong or what I should do. I only later learned that I was probably reported by the so called 50 Cent Army – professional internet commentators hired by the Chinese government to manipulate public opinions. Supposedly, they receive 50 cents for each comment, and is therefore known as the 50 Cent Party or 50 Cent Army. They recently started crossing the Chinese internet firewall in large numbers, not to obtain information, but to leave combative comments in various Hong Kong and Taiwan’s websites. According to news reports, one of their tactics is to report Facebook accounts of well-known critics of the Chinese government. This strategy has caused some of the critics their Facebook accounts. I was lucky enough to be able to verify my identity and save my account.

Then another thing happened. A well-known Hong Kong actor Wong Hei shared the news of my book on his Facebook page and also commented about Zhou’s hidden homosexuality. For this “severe crime,” Wong was punished by CCTV, a state television network where he had just finished filming a television show. CCTV announced that they would not cast him again and then blurred out his face in the show when it was aired.

What happened to me, compared with the Causeway Bay Bookstore Incident or Yiu’s case, is negligible. It is nevertheless a clear signal that no writer can survive when freedom of expression is suppressed. That is the current status of the press in Hong Kong under the rule of Chinese government. For now, Beijing’s suppression seems successful. But Hong Kong people will not give up their freedom without a fight. But that is another story.

* It was partially presented at PEN International Congress held in Ourense, Spain, on 28 September, 2016