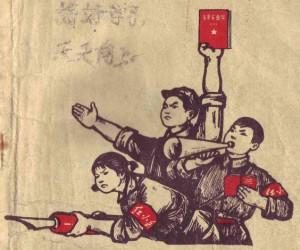

Three young Chinese Red Guards from the Cultural Revolution. Image via Wikimedia Commons.

The rhetoric of the 50th anniversary of the Cultural Revolution in China mirrors the Red Guard’s language of 1966.

May 16, 1966 marked the start of the Cultural Revolution in China. The Politburo of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party disseminated the so-called “May 16th Notification,” a document which illustrated the power struggle within the Party. Mao Zedong gained ascendancy and he used the opportunity to condemn his opponents and purge the “hidden bourgeoisie and revisionists” in the political, social, and cultural spheres. This originally ill-intended, later mutated mass movement has thrown China back to the Stone Age in civilization, pushed the economy to the edge of bankruptcy, crashed all the country’s traditional ethics and values, and destroyed the old architect and cultural relics. The rebellious Red Guards and their big-character posters with fanatic slogans became laughing stocks within the international community.

At the 6th Plenum of the 11th Central Committee on June 27, 1981, “the Resolution about Several Historical Issues since the Founding of Our State” was passed and the Cultural Revolution was officially negatively defined. Ye Jianying, the Marshal and chairman of People’s Congress, said during a Central Committee conference on December 13, 1978 that there were 20 million people killed and 100 million persecuted during the Cultural Revolution. If we exclude the remote rural population, this means nearly every family in the municipal area was affected. In fact, there is no Mainland-Chinese individual who I know who does not have several family members who were victims of the movement. Even though half a century has passed, somehow this issue is still taboo. One can criticize the “chaotic ten years” to a certain extent, but criticizing the founding father of the Cultural Revolution, Mao Zedong, would be considered a risk to his life.

For the 50th anniversary of the Cultural Revolution, we observe the “collective muting” of China’s media. Most of the print media has no space for this historical date. One exception is an article by Shan Renping at the official Global Times with the title, “Cultural Revolution has been totally rejected.” Renping argues that the Cultural Revolution was negative. He claims that the “class struggle” has ceased and that people have bid farewell to the idea of Cultural Revolution; it could not repeat in China again.

Another exception was an article published by People’s Daily, which asked people to “keep the historical lesson in mind and march further.” In this article, there is less reflection to the bloody and catastrophic upheaval but more encouragement to follow the beloved leader Xi Jinping and the Party to revive the great Chinese folk in realizing their dreams.

Both articles were published online at midnight on May 16, 2016. They did not aim to warn the public of the tragic happenings in the past; they were not shining pearls in darkness. The authors’ real intentions are not to come to terms with the past, to investigate the deep socioeconomic and political background of the movement, to expose the painful process of that turbulent decade, or to describe the fatal experience of the common people: the collapse of the economy and the capsizing of the whole educational system. What these two authors from the state-run media want is to play the trombone for Xi Jinping’s government – to ask citizens to become obedient subjects and to show loyalty to the leader and Party. “It is necessary that the Party, the country and all nationalities are combined as a rope, work together to eliminate all interference. Concentrate and work hard, to put our things run, to achieve our stated goal. Our thoughts and action should be united under the arrangement of the CCP Central, united under the spirit of Secretary General Xi Jinping’s important speech. Stick with the Party’s theoretical innovations to arm the Party and educating the people, guiding practice, have confidence to the road of socialism with Chinese characteristics, have confidence to the theory and system.”

This is not only a stereotype of flattery toward the Party mouthpiece – it smells very much like the language and spirit of the Red Guards in the Cultural Revolution. The CCP has never apologized publicly to the committed crime; rather, many victims’ family members received a letter, which announced the falsely persecuted person. If dead, the family would receive a small amount of compensation and if alive, he could return to his former job. My friend, Ms. Wang Rongfen, spent 11 years in prison because when she was a fourth year student at Beijing Foreign Language Institute, she wrote a letter to Chairman Mao on September 24, 1966 with these words: “Where is it that you are leading China? The Cultural Revolution is not a mass movement, it is one person using a gun to move the masses.” Wang survived and was released from prison after Mao’s death; she received 400 RMB for the 11 years of torture and imprisonment.

According to the official language the CCP is “glorious, great, correct,” so it could never make mistakes. It’s only “a handful of plotters” who dragged the Party into dirt, therefore there is no need to apologize. Consequently with millions of deaths and persecutions across the whole country, there are only victims and no perpetrators. In contemporary Chinese culture, confession, conscience, and a self-critical spirit are rare. Under the rule of violence, denunciation, egoism, and a culture of lies, people lost their feelings for honesty, dignity, respect, and leniency. Deng Xiaoping, a Chinese reformer, said, “Look forward,” to the Chinese people. This means forget all the bad memories and move further to a prosperous society. People replace that word “forward” with “money,” since both words have the same pronunciation in Chinese. Today, China is a country with money, but without justice. It shines, but without dignity.

On the eve of June 4, 2016, the 27th anniversary of the massacre at Tiananmen Square, Bao Tong, the political secretary of the former Prime Minister, Zhao Ziyang, was informed by the police that he should make himself ready for the trip, similar to many other “sensitive persons.” Each year around this date, the police will take him out of town for vacation, either in a tourist resort or he will be sent back to his hometown in Zhejiang province. “Clear up the capital city” is the police’s unofficial motto. Bao is used to it, along with many others, like Hu Jia, the human rights advocate, and Zhang Xianling, one of the “Tiananmen mothers.” This year the authorities are especially nervous because the anniversaries of the Cultural Revolution and Tiananmen Square are closely connected. Outside of China, in places such as Hong Kong, Europe, and North America, Chinese citizens are commemorating these two anniversaries in the hearts of many people inside China, remembering the dead and questioning the origin of the evil and crime that has never ceased. Someday there will be open ceremonies in China—this thought encourages citizens and tortures the perpetrator.