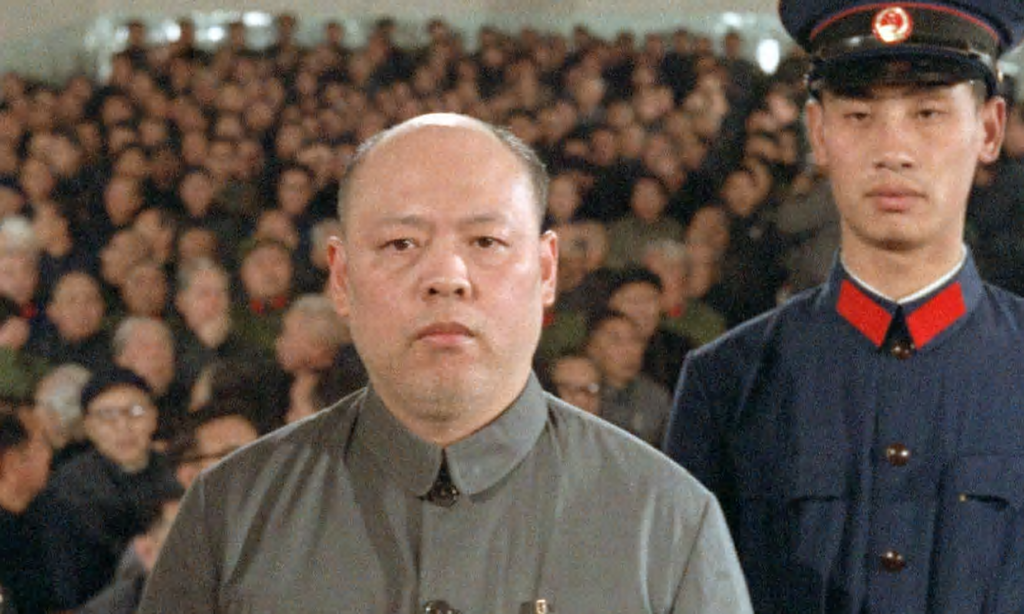

In 1966 — exactly 50 years ago this week — Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong made a sweeping edict: China would purge its corrupt capitalist remnants and awaken to a new era of Communist ideology, true and pure. In heeding the call of the Cultural Revolution, China’s youth formed Red Guard groups whose fierce adherence to Maoist ideology drove them to engage in an uncompromising purge of anything Confucian, Western, or bourgeois. For several years, violence wracked China’s cities.

In 1966 — exactly 50 years ago this week — Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong made a sweeping edict: China would purge its corrupt capitalist remnants and awaken to a new era of Communist ideology, true and pure. In heeding the call of the Cultural Revolution, China’s youth formed Red Guard groups whose fierce adherence to Maoist ideology drove them to engage in an uncompromising purge of anything Confucian, Western, or bourgeois. For several years, violence wracked China’s cities.

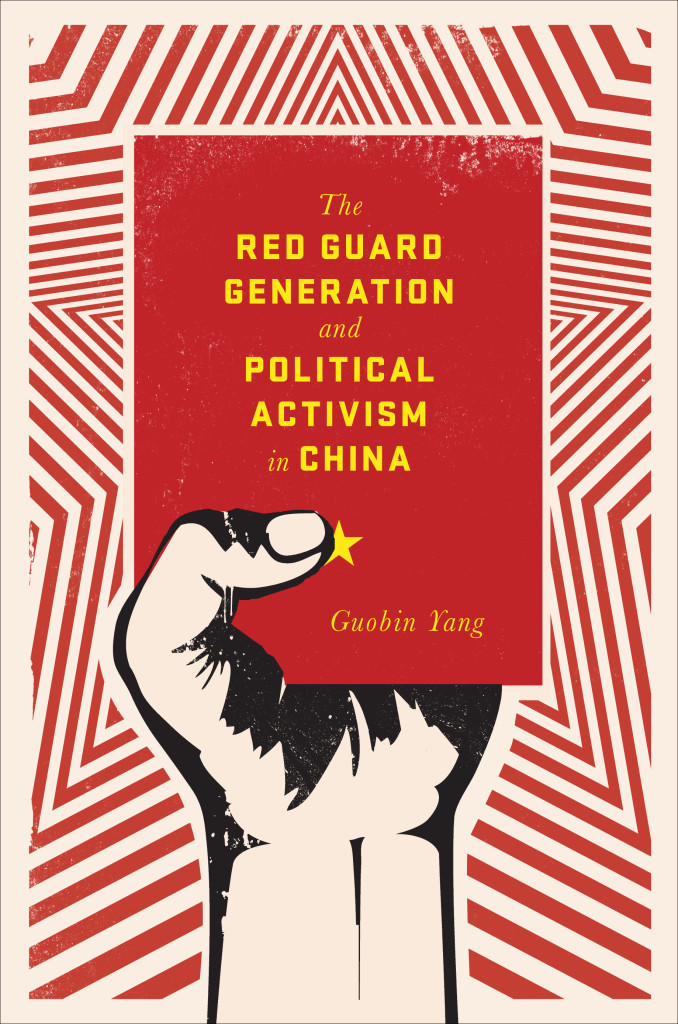

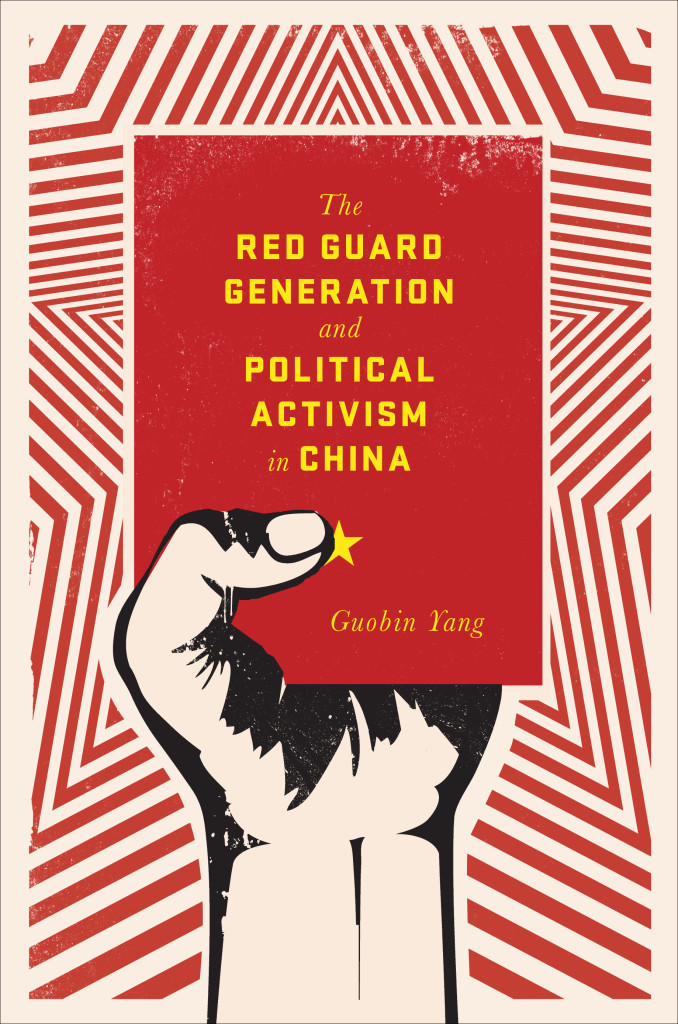

For young people coming of age at that time, life was profoundly different than that of generations before or since. In his new book, The Red Guard Generation and Political Activism in China, Professor Guobin Yang explores what happened to that generation and how their experiences shaped China for decades to come.

In the book, published by Columbia University Press, Yang argues that the forces that made the revolution also set in motion its undoing. After two years of fighting, millions of Red Guard were ordered by Mao to be “sent-down” to rural villages, partly as a means to control and curb the violence.

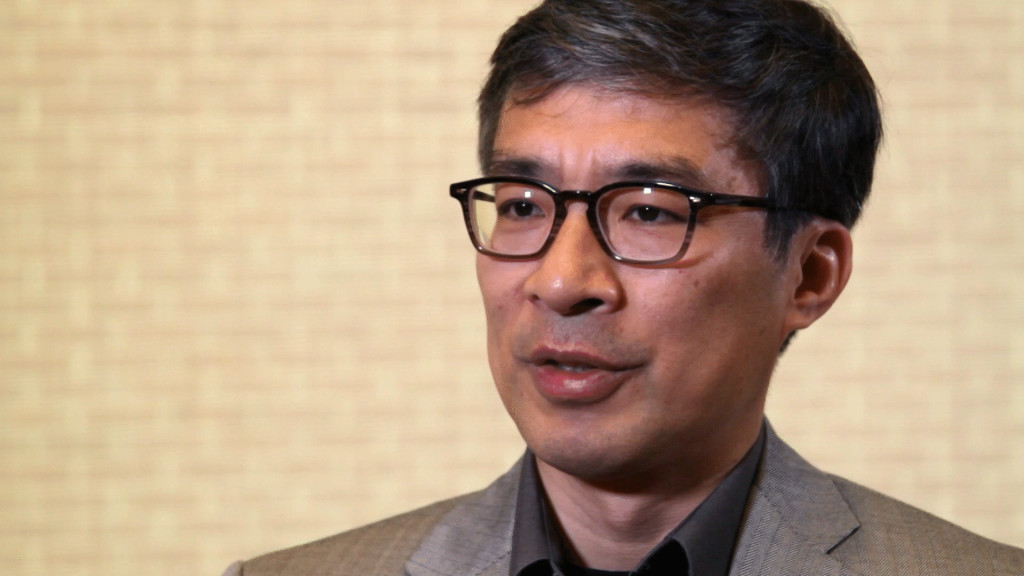

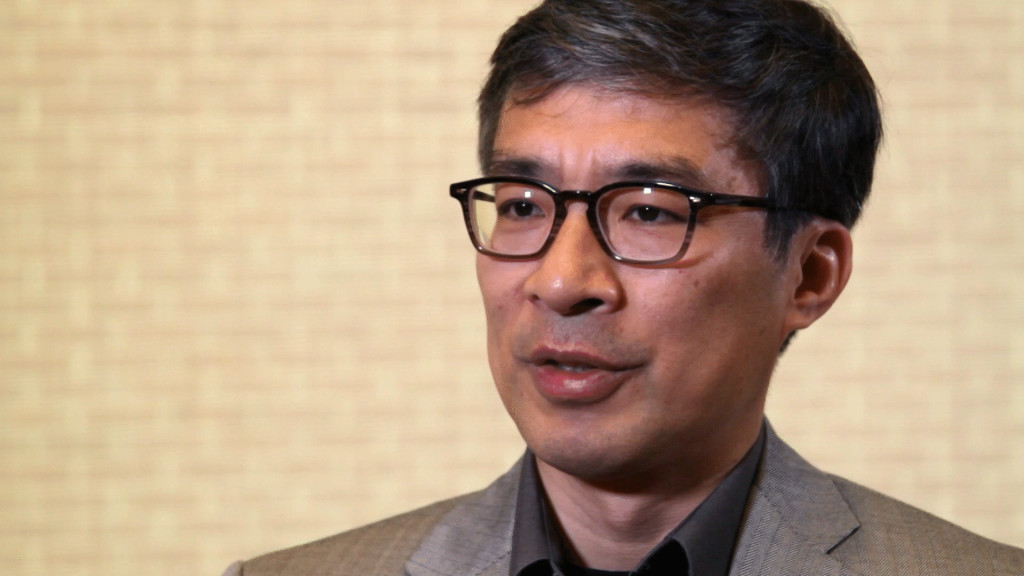

“The type of political culture they grew up in was one of loyalty to Mao, to the revolution, to struggle against class enemies, to the collective complete sacrifice of the self,” explains Yang, who is an Associate Professor of Communication and Sociology at Penn as well as a faculty member of the Center for the Study of Contemporary China and the Center for East Asian Studies. “But because of the violence, they had a sense of disillusionment. After all the fighting, nothing seemed to have been achieved.”

The sent-down youth were also woefully unprepared for the adjustment to rural life. They found rural China “backward” and were unprepared to become peasants. The revolution had used the slogan “Down with the self,” and considered real life personal concerns to be bourgeois. Yet, in one village, the village party secretary welcomed city youth’s arrival by telling them that “farming is for yourself.” The Red Guard generation was forced to think about its own day-to-day interests and came to appreciate the values of ordinary life rather than high-blown revolutionary ideals.

It was also the beginning of an underground culture as former Red Guards began to pick up their books again to re-educate themselves.

“They questioned the revolution and its meaning, gaining a new understanding of themselves, their society, politics,” says Yang. “Rural life was totally different than what they had learned in school before the Cultural Revolution.”

Such a generational transformation provides a foundation for both profound political and social change in China. Politically, Yang, says, the new outlooks of the Red Guard generation led to the first wave of popular protest for democracy from 1976 to 1980. This period marked the end of the Mao era and the beginning of the economic reform.

Guobin Yang, Ph.D.

In the book, Yang also makes a link from the sent-down youth to the beginning of economic reform in the late 1970s, which was a reversal of the Maoist planned economy. The government began to recognize private business, but faced resistance. Entrepreneurship had too long carried a moral stigma of dishonor.

“Because of the experience they had in the countryside, private enterprise was more acceptable to some members of the Red Guard generation,” says Yang. “Many of them had returned to the cities and couldn’t find jobs from the state. That understanding of personal interest and working for your own money and happiness had become acceptable to them. It laid a social foundation for the economic reform to take off. Otherwise it would have been harder to move from a planned to a market economy.”

In providing this new frame through which to view Red Guard activism, Yang concludes the book by looking at the politics of history and memory, arguing that the generation’s memories of that time often depend upon which side they happened to have been on 50 years earlier.

The release of Yang’s book, called “a major new study” by The Nation, coincided with the 50th anniversary of the beginning of the Chinese Cultural Revolution. As public debates about the contemporary ramifications of the Chinese Cultural Revolution exploded this month in the mainstream media, Yang’s book makes a timely scholarly contribution.

The Red Guard Generation and Political Activism in China is available now from Columbia University Press.

Source: https://www.asc.upenn.edu/news-events/news/new-book-guobin-yang-explores-red-guard-generation-china

In 1966 — exactly 50 years ago this week — Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong made a sweeping edict: China would purge its corrupt capitalist remnants and awaken to a new era of Communist ideology, true and pure. In heeding the call of the Cultural Revolution, China’s youth formed Red Guard groups whose fierce adherence to Maoist ideology drove them to engage in an uncompromising purge of anything Confucian, Western, or bourgeois. For several years, violence wracked China’s cities.

In 1966 — exactly 50 years ago this week — Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong made a sweeping edict: China would purge its corrupt capitalist remnants and awaken to a new era of Communist ideology, true and pure. In heeding the call of the Cultural Revolution, China’s youth formed Red Guard groups whose fierce adherence to Maoist ideology drove them to engage in an uncompromising purge of anything Confucian, Western, or bourgeois. For several years, violence wracked China’s cities.