From Wang Shiwei to Liu Xiaobo: Prisoners of Literary Inquisition under Communist Rule in China

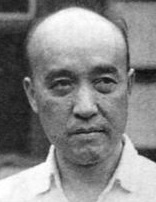

Hu Feng (born Zhang Mingzhen, November 2, 1902 – June 8, 1985), a prominent art and literary critic, commentator, editor, translator and poet, was imprisoned in 1955 after the authorities named him leader of a“Hu Feng Counterrevolutionary Clique” on the basis of a “300,000-word Report”. He spent 24 years in prison and six more years under the cloud of injustice until his death.

Hu Feng (born Zhang Mingzhen, November 2, 1902 – June 8, 1985), a prominent art and literary critic, commentator, editor, translator and poet, was imprisoned in 1955 after the authorities named him leader of a“Hu Feng Counterrevolutionary Clique” on the basis of a “300,000-word Report”. He spent 24 years in prison and six more years under the cloud of injustice until his death.

Acquainted with Wang Shiwei at Peking University

Hu Feng was born to a peasant family in Qichun County, Hubei Province. Poverty delayed his formal schooling until the age of 11, and his mother died soon after that. At the age of 17, Hu Feng began attending public school in the county seat, but he dropped out due to his dissatisfaction with the school’s antiquated teaching methods. He was admitted to middle school in Wuchang and then in Nanjing, and joined the Chinese Communist Youth League in 1924. By then he had publishing an essay on improving Hubei’s education system in a supplement to Beijing’s Morning Post, followed by a short story, “Two Representatives of Union Branch”, in a supplement to The Republican Daily News (Minguo Ribao) in Shanghai.

Hu Feng studied literature at Peking University in 1925 (with Wang Shiwei, who would later become a fellow victim of the literary inquisition) and then Western literature at Tsinghua University in 1926, but discontinued his studies to take part in the Northern Expedition campaign as secretary-general and standing member of the Qichun county committee of the KMT. The year 1927 saw him moving between teaching and various propaganda and publishing posts within the KMT and ending up in Nanchang as deputy editor of a supplement to the official Republic Daily.

The Left Coalition of Writers and the Great Slogan Debate

In autumn 1928, Hu Feng left Nangchang for Shanghai to prepare his study in Japan, and he published a number of short stories and poems during the following year. He then went to Japan to study Japanese at his own expense in September 1929. In spring 1931, he became a semi-state funded student at the English Department of Keio University, and then involved himself in a number of cultural and political groups such as the Arts Research Society of the Japanese Proletarian Culture League, the Japanese Communist Party, the Tokyo Branch of the China League of Left-Wing Writers (Left League or Zuolian) and the “Emergent Culture Research Society” (Xinxing Wenhua Yanjiuhui) organized by other Chinese students. He published his first translation of a Soviet novel, Marietta Shaginyan’s Mass Mend: Yankees in Petrograd, in Shanghai in 1932.

In May 1933, Hu Feng was expelled from Japan for attending the activities of Japan’s Leftist movement, including a memorial for the death of Kobayashi Takiji in prison. Back in Shanghai, he joined the Left League as propaganda head and then administrative secretary, and editing the mimeographed publication Literary Life (Wenxue Shenghuo), leading to a close relationship with Lu Xun. He also served as a translator of Japanese for Classified Current Affairs (Shishi Leikan), a magazine under the KMT’s Sun Yat-Sen Institute for the Advancement of Culture and Education.

In autumn 1934, Hu Feng resigned from his positions at both the Institute and Left League after Left League CPC group secretary Zhou Yang and others accused him of being a “traitor.” Turning full-time to writing, he used the pen name Hu Feng for the first time for his essay “On Lin Yu-tang”, published in Literature Magazine. At the end of the year, he married Mei Zhi.

In 1935, Hu Feng edited a covertly published series of books, Sawdust Series (Muxue Wencong), including novels and Soviet literary and arts theory. In May of that year, he published an article on the question “What Are ‘Prototype’ and ‘Style’?”, which was soon criticized by Zhou Yang, starting their first debate on artistic theory.

In February 1936, he joined Nie Gannu, Xiao Jun, Xiao Hong and others, supported by Lu Xun, in establishing the literary magazine Petrel (Haiyan). In June, he published an essay “What Do the Masses Demand of Literature?” in Journal of Literature, promoting the slogan of “Mass Literature of the National Revolutionary War”, which he had formulated together with Lu Xun as well as Feng Xuefeng, an emissary of the CPC Central Committee in Yan’an. He again came under criticism by Zhou Yang, who with others had earlier proposed the slogan of “National Defense Literature”, leading to the “Two Slogans debate”. In the same year, He also published a collection of translated Korean and Japanese short stories and two collections of criticism.

The July School and the Mainstream Faction

Lu Xun died in October 1936, and in 1937, Hu Feng collected his posthumous writings in the Work and Study Series of books, while also publishing his own first poetry collection, Wild Flowers and Arrows (Yehua Yu Jian). After the War of Resistance against Japan broke out on July 7, Hu Feng founded and edited the magazine July, which experienced interruptions due to the Japanese occupations on Shanghai and Wuhan, where he took refuge one after another. The magazine finally closed down in Chongqing in July 1941, but Hu went on to edit and publish the July Poetry Series and the July Essay Series, fostering what came to be known as the “July school” of modern literature.

In March 1938, the All-China Anti-Japanese Association of Writers and Artists was established in Wuhan, and Hu Feng was elected the association’s executive director and deputy head of its research department. This was followed by a short stint as editor of the Sunday arts page of the CPC’s New China Daily (Xinhua Ribao) , along with publication of another volume of criticism. In December, Hu Feng took his wife and son to Chongqing to serve as visiting professor at Fudan University (which had also temporarily moved there from Shanghai). With the birth of his daughter in early 1939, Hu Feng took on extra work as a translator of Japanese for the international publicity section of the KMT’s propaganda department.

A new debate with CPC “mainstream” writers arose in 1940 when Hu Feng published his theoretical monograph On the Question of National Form, and he followed up the following year with a volume of essays covering both sides of the debate. In October 1940, the third bureau of Political Department at the national government’s Military Commission was reorganized into a Cultural Work Committee, and Zhou Enlai, at that time the deputy head of the department as well as secretary of the Southern Bureau of the CPC Central Committee, arranged for Hu Feng to serve as a full-time committee member.

In June 1941, Zhou Enlai arranged for Hu Feng and his family to move to Hong Kong, but they relocated to Guilin the following March after Hong Kong came under Japanese occupation. It was in Guilin that Hu Feng began editing the July Poetry Series. He also published a collection of commentaries, National Warfare and the Artistic Nature, and a second collection of poetry, Songs for the Motherland, along with a collection of translations, Humanity and Literature.

In May 1942, CPC leader Mao Zedong published his “Talks at the Yan’an Forum of Literature and Art” (hereafter “Talks”), which immediately became the CPC’s guiding policy for rectifying and unifying the ideology of Leftist writers and artists.

Hu Feng returned to Chongqing in March 1943 to prepare for publication of Hope Magazine. Zhou Enlai provided the magazine with CPC funding, but Hu maintained an independent line of literary theory and expressed alternative views on the application of the “Talks”, leading the CPC leadership and its mainstream writers to consider him one of the most problematic of the Left-wing literati.

In the first issue of Hope in January 1945, Hu Feng published Shu Wu’s long philosophical essay “On Subjectivity”, which the CPC saw as openly confronting the spirit of the “Talks”. This launched a multi-year debate between the Leftist mainstream and July School of writers.

In February 1946, Hu Feng returned with his family to Shanghai, where he continued running Hope Society (Xiwang She), producing periodicals and book series and publishing collections of his criticism as well as a translation of the novelette Cotton by the Japanese Communist Taniguchi Zentaro.

Hu Feng and other members of the July School came under attack by Popular Literature and Art Series, founded by mainstream CPC writers in in Hong Kong in 1948. Hu Feng delivered a comprehensive rebuttal in his monograph On the Realist Road.

Time Has Begun

At the end of 1948, the CPC Central Committee invited Hu Feng and some other pro-Communist notables in Shanghai to the “Liberated Areas” in northern China, and Hu took part in preparations for the NCLAW in the newly liberated capital at the end of March 1949. In July, he was elected to the national committee of NFLAW and to the standing committee of the subsequently established NALW, and he attended the national committee meeting of the CPPCC. However, his plan to publish an epic poem entitled “Time Has Begun” in the People’s Arts supplement of People’s Daily was curtailed after the first installment on November 20, and his publication of the other portions in alternative venues quickly brought him under criticism.

Within the space of one week in March 1950, People’s Daily published two articles criticizing another key theorist of the July School, Ah Long, who also came under censure in the Ministry of Culture. Zhou Yang, now deputy director of the Central Propaganda Department, asserted that Ah Long was part of a “petty bourgeois writers’ faction”. This was the prelude to the purge of the “Hu Feng Clique”.

Hu Feng went on to publish a collection of criticism, For Tomorrow (1950), two essay collections, the epic poem “For Korea, For Humanity”, and a collection of reportage, With the New People (1952).

In early 1952, an internally circulated edition of Literary Gazette published a series of letters from readers demanding further criticism of Hu Feng’s literary thought. This was followed in September by Shu Wu’s “Open Letter to Lu Ling”, in which Shu turned against his old ally, and the editor’s note of which accused Lu Ling of belonging to a “literary faction led by Hu Feng”, “the fundamental line of which runs counter to the proletarian literary line led by the Party – Mao Zedong’s literary and artistic orientation”. Zhou Yang took this assertion a step further in December during a forum for writers and artists to “help” Hu Feng recognize his problems: “Hu Feng’s literary theory follows an anti-Party line”.

Literary Gazette continued to publish criticism of Hu Feng in 1953, including “Hu Feng’s Anti-Marxist Literary Thought” by Lin Mohan, a deputy head of the CPC Central Propaganda Department’s Literature and Art Section. People’s Daily reprinted Lin’s article with an “editorial note”. Hu Feng wrote to Premier Zhou Enlai voicing his objections, and Zhou arranged for him to join the editorial committee of People’s Literature (Renmin Wenxue).

In August 1953, Hu Feng and his family moved to Beijing, and he and Lu Ling continued taking part in the second NCLAW and other national cultural associations. However, Ah Long and other writers of the July School who had attended the first Congress were not invited this time.

From the “300,000-word Report”

to the “Hu Feng Counterrevolutionary Clique”

In the first half of 1954, Lu Ling’s novels and essays came under renewed attack in national publications and by Zhou Yang in meetings, and Hu Feng, Lu Ling, Ah Long and others prepared a counter-attack in the form of a “Report on the Practical Situation of Art and Literature Since Liberation” (hereafter the “300,000-word Report”). This report rebutted the various criticisms and accusations against them and other writers in recent years, declared their stands on some aspects of literary theory, pointed out problems with the arts authorities and their work, and offered some suggestions. Other July School writers also made written submissions. In July that year, Hu Feng delivered his “300,000-word Report” to the State Council’s Culture and Education Committee to pass on to the Politburo of the CPC Central Committee, after which he attended his first meeting as a deputy to the first National People’s Congress in September.

In January 1955, the Central Committee endorsed a nationwide propaganda campaign criticizing Hu Feng’s ideology. People’s Daily followed up with an article by Shu Wu on “The Anti-Party, Anti-People Essence of Hu Feng’s Literary Thought”, with extracts of correspondence between Shu Wu and Hu Feng in the 1940s and an editorial note subsequently attributed to Mao. Early in the morning of May 17, the Public Security Bureau searched Hu Feng’s home and took Hu and his wife, Mei Zhi, into custody. Formal arrest followed the following day, after which People’s Daily published batches of letters seized from the homes of Hu and his friends. A nationwide investigation of the “Hu Feng Counterrevolutionary Clique” was launched with the arrest of many “Hu Feng Elements”. In July and November that year, the Central Propaganda Department and Ministry of Culture banned the publication of “works and translations by Hu Feng and core members of the Hu Feng Clique”.

The Hu Feng case was the first nationwide literary inquisition undertaken by the CPC since taking power, and the largest of such campaigns in China’s history. An official reexamination of the case in 1980 found that more than 2,100 people were investigated, 92 arrested, 62 placed in isolation and 73 suspended from their duties. The actual number of people implicated greatly exceeds these official figures, and in the Anti-Rightist Campaign that followed, people who criticized the authorities’ handling of the case were labeled Rightists and even counterrevolutionaries. The devastating effects of this case led to the disappearance of independent writers’ circles for the next 20 years.

Although public security officials tried their hardest to find evidence, nothing in the recent or past activities of Hu Feng and the others suggested counterrevolutionary crimes; rather, an abundance of counterevidence demonstrated their contributions to the Communist “revolution”. Since the authorities had already published the “proof of crime” and verdict, however, no one dared refute it, and Hu Feng remained in prison without his case being brought to a close.

On December 26, 1965, more than ten years after his arrest, Hu Feng was sentenced to 14 years’ imprisonment as “ringleader of a counterrevolutionary clique”. Given his age and frailty, he was released to serve the remainder of his sentence outside of prison. The authorities forced him to return to Sichuan with Mei Zhi, and the couple was sent to the Miaoxi Labor Reform Tea Farm in Lushan County.

By then the Cultural Revolution had begun, and in November 1967, Sichuan’s Provincial Revolutionary Committee had Hu Feng sent back to prison. Although he had completed his 14-year sentence, Hu was sentenced to a life term in January 1970 for the counterrevolutionary crime of “writing a reactionary poem on Chairman Mao’s portrait”. He suffered mental collapse and attempted suicide several times.

In January 1973, 60-year-old Mei Zhi was sent to the Sichuan No. 3 Prison in Dazhu County to look after her physically and mentally devastated 70-year-old husband. Under her care, Hu Feng’s condition gradually stabilized.

Loose ends

With the death of Mao Zedong and the ending of Cultural Revolution, the Sichuan Provincial Public Security Bureau released Hu Feng in January 1979 and settled him in Chengdu. The fourth NCLAW convened in September that year, but Hu Feng was barred from attending because he was not yet rehabilitated. He suffered another mental collapse and in March 1980 obtained permission to receive treatment in Beijing. Having partially recovered, he began petitioning for his 1965 conviction to be overturned. On September 29, 1980, the CPC Central Committee endorsed the reexamination report on the Hu Feng Counterrevolutionary Clique by the Ministry of Public Security, the Supreme People’s Procuratorate and the Supreme People’s Court and acknowledged the injustice done, rehabilitating all members of the “clique”. This allowed the Beijing Intermediate Court to vacate Hu Feng’s 1965 conviction, but the Central Committee retained a negative conclusion relating to Hu Feng’s literary thought, “sectarian activities” and past political problems.

In November 1980, Hu Feng published his first essay in 26 years in Wenhui Monthly, “Greetings to Friends and Readers”. A year later, he was appointed to the standing committees of the CPPCC and the CFLAC and as an adviser to the CWA, the National Academy of Arts and other bodies. He went on to publish three volumes of his collected commentaries, and had just written an essay entitled “Why I Write” for the Paris Book Fair and the Swiss newspaper 24 heures when he fell seriously ill on March 14, 1985. He died of cancer on June 8 at the age of 83.

Hu Feng went to his grave with the Central Committee’s residual allegations hanging over his head, and for that reason, his family rejected any attempt by the authorities to eulogize him. Finally, in November 1985, the CPC Central Committee Secretariat approved withdrawal of the allegations of “historical problems”. Although a few issues remained unresolved, the compromise allowed a memorial service to be held for Hu Feng the following January.

On June 18, 1988, CPC Central Committee’s General Office formally revoked all remaining allegations and restored Hu Feng’s good name.

In 1999, Hubei People’s Publishing House produced The Complete Works of Hu Feng in ten volumes totaling 5.5 million characters.

Bibliography

- Wu Xiaoming, “Hu Feng’s Pseudonymous Miscellany”, 1985.

- Xiao Feng, “Hu Feng Concise Chronology”, 1986.

- Senno Takumasa and Zhu Xiaojin, “Hu Feng’s Bound to Current Affairs”, 1992.

- Hu Feng, The Memoirs of Hu Feng, 1993.

- Xu Lin’en, “Hu Feng’s First Work”, 1994.

- Dai Guangzhong, The Biography of Hu Feng, 1994.

- Mei Zhi, The Biography of Hu Feng, 1998.

- Sun Zhen, “The Ins and Outs of the ‘Hu Feng Case,’” 2000.

- Zhang Liangsen, “Hu Feng’s Editing and Publishing Career”, 2002.

- Li Hui, The Whole Story of the Unjust Hu Feng Clique Case, 2003.

- Li Hui, “1955 Banned Books”, 2003.

- Shi Yun and Li Xin, “The Wrongful Hu Feng Case from Beginning to End”, 2003.

- Zhou Zhengzhang, “Hu Feng’s Memorial and Three Rehabilitations”, 2004.

- Hu Xuechang, “The Origin of the Hu Feng Incident”, 2004.

- Zheng Wenlin, “The Similar Lessons of the Unjust Hu Feng and Wang Shiwei Cases”, 2006.

- Mei Zhi, Journal of a Prison Companion: Hu Feng and I, 2008.

- Dai Zhixian, “The Whole Story of the Hu Feng ‘Counterrevolutionary Clique,’” 2008.

- Wu Yongping, “Two Important Newly Discovered Documents Regarding Hu Feng”, 2010.

- Xiao Gu, “Recollection of Historical Truth: A Reply to Mr. Shang Jinlin”, 2010.

- Su Xiaohe, “Prisoner Hu Feng”, 2012.

Translated by Stacy Mosher