2025年1月17日

编者按:本月作家為作家、纪录片导演周勍。艾未未看完其纪录片《我记不清了》评价说:剪的挺好,内容也挺好的,就是说,比我想象的都要更实在一些,不糙!看上去不糙。片头开始说:“大家都不记得了”这个也挺好的,大概就这么个事儿。纪录片介绍后同时推介其报告文学《民以何食为天》的新版自序《没有痛感,就会被淘汰》。

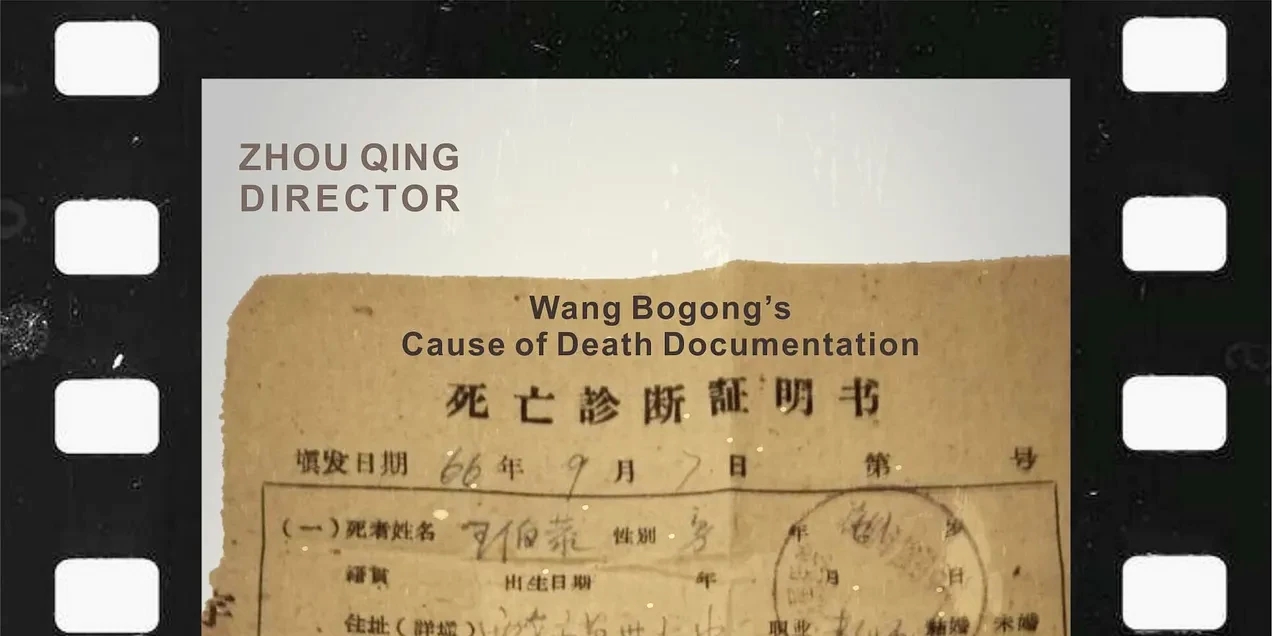

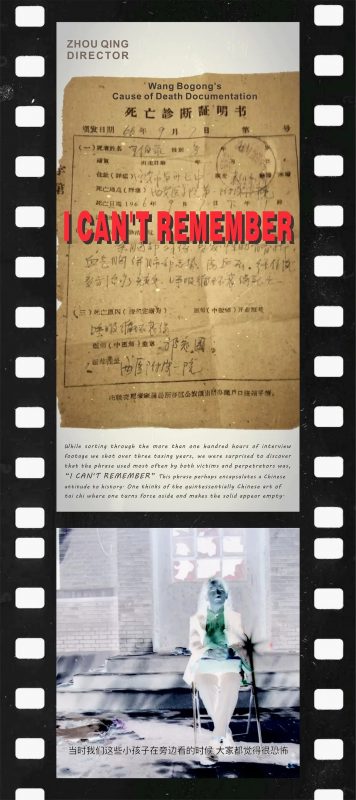

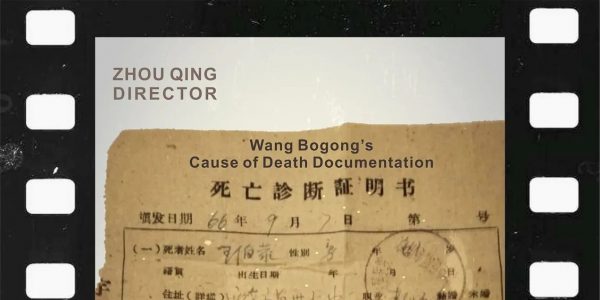

纪录片:《我记不清了》

导演:周勍

内容简介 (时长:87分钟 )

受访者之一编剧芦苇(芦苇为中国著名编剧,主要作品有《霸王别姬》、《活着》、《图雅的婚事》和《狼图腾》等)。

我是西安市37中的,文革中我们学校学生一天之内打死两个、打伤了九个、打残废了一个、精神失常一个老师。打死的男老师叫王伯恭,女老师叫王冷。凶手的年龄12至16岁,王冷是有着数百万人口的西安市文革中的第一个被打死的教师。

五十年过去了,我们不仅是重现那场暴行。更为重要的是,中国人怎样对待“文化革命”这样一个近期的历史事件:当事者现在以什么样的态度对待?以及怎样谈论过去?那些与迫害王冷有关的人当谈及这件事时如何反应?

主人公是中国著名编剧芦苇和王保民。 王当时被迫参加批斗会,否则就有被列入反革命分子或者黑帮子弟行列的危险。他亲眼目睹王老师被施酷刑的过程。芦是黑帮子弟,没有参加批斗会的资格。 王说:“我当时要是能大喊一声‘住手!’,或者离开会场,王老师或许就不会死。但是我没有这样做。我只能悄悄流泪,我也是可耻的看客。”

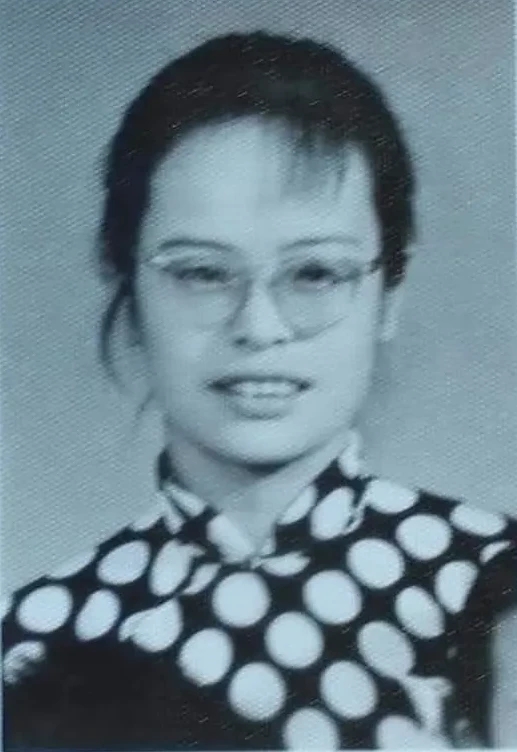

王保民活着,芦苇活着。毛死了。中国发生了变化。生活是艰难的。一切都在飞速变化。但是,芦和王的生活中只有一点没有变: 那就是王老师之死的回忆。这回忆以及与此相连的反思过去的迫切感,王执着地寻找,终于找到了王老师的女儿。 王的女儿叫张晔。母亲被打死时她才十三岁。王保民多年来一直和张晔联络。张现在63岁。 王保民现在退休了,他用自己的时间来回顾历史。为此,他去寻找当年的同学,一些是证人,一些是凶手。他设法同他们谈起这个话题。

芦苇在一个当年的同学聚会上提议搞一个特别的纪念王冷老师的聚会,他提议大家每人写一篇回忆王老师的文章,出一本纪念册,期望通过这个活动得到王老师家人的原谅,得到心灵上的安宁。可惜,除了一女同学写了纪念文章,其他参会的同学全部拒绝。

张晔在她的微博上开了专栏,和一些人共同讨论和反思毛泽东时代。这是共产党不愿意提的事,会受到检查。张晔认为,如果不对毛清算,中国就没有前途。她的论坛一再受到封闭。但是,张坚定不移。她自己也永远不能忘记见她妈妈最后一面的情景。那恐怖的场面永远无法在她眼前消失。张晔为自己的活动也付出了代价。 白解放和邵桂枝是参与迫害王冷行动的人。王保民一再请他们谈谈当时的情况。他们起初答应,后来又拒绝了。王最终和他们通了电话,并找到了他们的照片。

在整理历时三年多拍摄所得的一百多万字的素材时,意外的发现在这一事件中,无论是受虐者还是施虐者,加上标点符号,重复最多的一个词句就是“我记不清了”——而这句话可能就是中国人面对历史时的态度。

Synopsis of the ‘I Don’t Quite Recall’

Born in March 1950, interviewee Lu Wei is a screenwriter, and his major works include Farewell My Concubine (1993), To Live (1994), Tuya’s Marriage (2006), and Wolf Totem (2015).

Lu: I was a student at what was then Xi’an No.37 Middle school in the 1960s. During the Cultural Revolution, two of our teachers were beaten to death on the same day, and another nine were injured. One teacher was left disabled, and another lost their mind due to the torture and beatings. The two teachers who were killed were Wang Leng and Wang Bogong. The murderers were their very own students, aged 12 to 16 years old at the time. Wang Leng was the first teacher killed when the Cultural Revolution started in Xi’an, a provincial capital city with a population of several million.

More than fifty years have passed since. We are not looking to simply revisit the circumstances of their deaths and the wider context; we also seek to address several other questions. Most importantly, how do the Chinese people deal with the Cultural Revolution, given that it is such a recent historical event? What attitudes do those at the center of the action take when looking back on what happened? What are their narratives of this past? As one significant example of the many major consequences of the Cultural Revolution, how do those involved in Wang Leng’s death react when asked to recount these events?

The two main narrators of this story are Lu Wei and Wang Baomin. They were both students of Wang Leng at the time of her death. Wang Baomin was obliged to participate in the struggle sessions against Wang Leng or risk being labelled as a “counter-revolutionary” or “bad class element.” This meant he witnessed the beating, torture, and death of Wang Leng. Lu Wei had already been labelled a “bad class element” and excluded from the struggle sessions. Wang Baomin later said, “If I had just once yelled out ‘stop’, perhaps Ms. Wang would not have died that day. I didn’t, I only cried quietly, which makes me also a shameful bystander to the whole business.”

Wang Baomin and Lu Wei are still alive today, though Chairman Mao is long dead. China has gone through major changes. Life can be tough, and everything is evolving at a breakneck pace. Yet after many years, one thing remains common and constant in the lives of Wang Baomin and Lu Wei: their shared memories about the death of their teacher Wang Leng. These memories and the need to reflect on the past compelled Wang Baomin to seek out Zhang Ye, the surviving daughter of Wang Leng. It was no easy task, but eventually, Wang Baomin was able to contact Zhang Ye, and the pair have stayed in touch ever since. Zhang Ye was just thirteen when Wang Leng was killed by her students. Now she is sixty-three.

Wang Baomin is retired now. He uses his now ample free time to revisit this period in history. To this end, he has sought out former schoolmates, some who were more witnesses and some who were killers. Wang has tried to raise the subject many times in their conversations. Lu Wei also once suggested that their middle school reunion hold a special ceremony to commemorate Wang Leng. He asked everyone present to write a remembrance about their teacher, which could later be collected and published. Lu saw this as a way to ask for forgiveness from Wang’s family and to make peace with their own consciousness and sentiments. Only one classmate wrote a remembrance; all the others refused.

Zhang Ye has a Weibo microblog account. She tries to discuss and reflect on the Mao era with others online. This is not something the Party wants, and discussion is heavily censored. Zhang Ye believes that if the Chinese people don’t expose and criticize Mao Zedong, China as a nation has no hope for a future. Zhang Ye’s Weibo account has been repeatedly closed, but she is determined to continue. She cannot forget the last time she saw her mother, a gruesome scene that will haunt the rest of her days. Zhang Ye says she is willing to accept the consequences of her actions.

Bai Jiefang and Shao Guizhi were also students or colleagues of Wang Leng. They, however, were among those who participated directly in the events leading to her brutal death. Wang Baomin asked several times if they would be interviewed about what happened in our film. They were open at the beginning, but all refused afterward. Wang was eventually able to interview them by phone and find current pictures of the pair.

While editing a large amount of footage for this project over the past three years, it struck me that a common phrase among the millions of words written from various perspectives, good people and bad, about the Cultural Revolution is “I don’t quite recall.” Those words might encapsulate the Chinese attitude toward recent history.

凡是反动的东西,你不打,他就不倒。这也和扫地一样,扫帚不到,灰尘照例不会自己跑掉。 ——毛泽东

主题::文革的恐怖与中国对历史的反思

1966年8月18日, 毛泽东在天安门广场接见了一百万大学生和中学生,发动了所谓的“文化大革命“。毛要求中国的年轻人,红卫兵,展开一场破除旧风俗习惯,揭发批判走资派的运动。

毛的批判对象是有一定权威的人:老师、教授、知识分子及老干部。那些本来注重自己孩子教育的中国孩子的父母亲们,开始为自己的生命担忧,因为,他们的孩子们随时都有出卖他们的可能。

中共自己承认,在毛的十年文革中,有两千万人非正常死亡。

情节和人物

这是个关于陕西西安第37中学当年36岁的女教师王冷的故事。毛泽东发动文革两星期后,她在一场批斗会中,当着上千人的面被活活折磨死。还有另外一名教师被打死,二十多名被打伤。凶手的年龄12至16岁。王冷是有着数百万人口的西安市文革中的第一个被打死的教师。

五十年过去了。一位当年的学生,暴行的见证者,要用自己的行动来防止这个暴行以及其它暴行被人们忘记,或者永远忘记。

影片的中心不是重现那场暴行。更为重要的是,中国怎样对待“文化革命”这样一个近期的历史事件的问题。当事者现在以什么样的态度对待,以及怎样谈论过去?那些与迫害王冷有关的人当谈及这件事时如何反应?

影片的主人公是中国著名编剧芦苇和王保民。

王当时被迫参加批斗会,否则就有被列入反革命分子或者黑帮子弟行列的危险。他亲眼目睹王老师被施酷刑的过程。芦是黑帮子弟,没有参加批斗会的资格。

王说:“我当时要是能大喊一声‘住手!’,或者离开会场,王老师或许就不会死。但是我没有这样做。我只能悄悄流泪,我也是可耻的看客。”

王保民活着,芦苇活着。毛死了。中国发生了变化。生活是艰难的。一切都在飞速变化。但是,芦和王的生活中只有一点没有变:

那就是王老师之死的回忆。这回忆以及与此相连的反思过去的迫切感,王执着地寻找,终于找到了王老师的女儿。

王的女儿叫张晔。母亲被打死时她才十三岁。王保民多年来一直和张晔联络。张现在63岁。

王保民现在退休了,他用自己的时间来回顾历史。为此,他去寻找当年的同学,一些是证人,一些是凶手。他设法同他们谈起这个话题。

芦苇在一个当年的同学聚会上提议搞一个特别的纪念王冷老师的聚会,他提议大家每人写一篇回忆王老师的文章,出一本纪念册,期望通过这个活动得到王老师家人的原谅,得到心灵上的安宁。可惜,除了一女同学写了纪念文章,其他参会的同学全部拒绝。

场景

.芦苇、王保民去见同学的路上,在和他们谈话,在茶馆,在路上,广场上。 王一个人在旧货摊上寻找文革资料原件。

张晔在她的微博上开了自己的专栏,和一些人共同讨论和反思毛泽东时代。这是共产党不愿意提的事,会受到检查。张晔认为,如果不对毛清算,中国就没有前途。她的论坛一再受到封闭。但是,张坚定不移。她自己也永远不能忘记见她妈妈最后一面的情景。那恐怖的场面永远无法在她眼前消失。张晔为自己的活动也付出了代价。

白解放和邵桂枝是参与迫害王冷行动的人。王保民一再请他们谈谈当时的情况。他们起初答应,后来又拒绝了。王最终和他们通了电话,并找到了他们的照片。我们可以在影片中使用这些资料。

风格

不采用表演还原的方式。而使用相关人的生活镜头。

采访(说及文革的时候,常常可以观察到被采访人的恐惧)。

街景。通过这些街景可以看出毛泽东及文革今天在中国的地位; 出租车里作为保佑者的毛的肖像,公园里满怀激情唱红歌的人,以文革为主题的餐饮业,等等。

来源:波士顿书评