by Harrison Lee on Monday, May 12, 2014

Japanese manga/anime covers, in a Sina Weibo post reporting that Chinese video site licensing of Japanese anime has come to a halt following recent Chinese government policy.

by Harrison Lee on Monday, May 12, 2014

Japanese manga/anime covers, in a Sina Weibo post reporting that Chinese video site licensing of Japanese anime has come to a halt following recent Chinese government policy.

Chinese Video Websites Halt Buying of Japanese Anime已关闭评论

Posted in Headlines

Tagged Internet Freedom, Video Websites

While code language emerges online as a response to government-blocked words, censorship regulators are increasingly finding ways to decode that language. Future SIPA courses hope to explore digital media surveillance in today’s world

Digital Activism: Blocked on Weibo, Encouraged at SIPA已关闭评论

Posted in Headlines

Tagged Internet Freedom, Weibo

By China Change, published: May 18, 2014

TANG JINGLING (唐荆陵)

In Guangzhou, renowned rights lawyer Tang Jingling (唐荆陵) was criminally detained on May 16, for “provoking disturbance,” according to weiquanwang, a primary website reporting on China’s rights defense events.

Two More Rights Lawyers Criminally Detained, Another’s Home Searched已关闭评论

Posted in Headlines

Tagged Human Rights Lawyer, Jiang Tianyong, June 4th, Liu Shihui, Tang Jingling, Tiananmen

By AMY QIN JANUARY 6, 2014, 4:02 AM 17 Comments

Associated Press

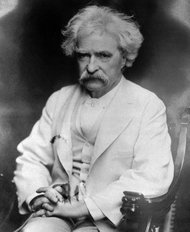

For decades, one of Mark Twain’s satires of American politics was required reading in Chinese schools.

There are few authors regarded as quintessentially American as Mark Twain. With his preternatural gift for capturing vernacular expression and his roguish wit, Twain is still widely seen as the founder of the American voice. More than a century after his death, “The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn,” Twain’s most celebrated work, remains a mainstay of middle school and high school English classes. Ernest Hemingway famously declared it the book from which “all modern American literature comes.”

Twain’s writings have won him literary fame in China as well. Although “Huckleberry Finn,” with more than 90 different translations in Chinese, is a favorite, a large portion of Twain’s popularity in China derives in fact from another, much more obscure work: a short story called “Running for Governor.”

A humorous account of Twain’s fictional candidacy in the 1870 New York gubernatorial election, “Running for Governor” was taught alongside the writings by Mao Zedong and other prominent Chinese thinkers and literary figures in middle schools across China for more than 40 years. In this time, it was read by several generations and millions of Chinese, making Mark Twain one of the best-known foreign writers in China and “Running for Governor” one of his best-known works.

“Just about anyone who has had a middle-school education in China knows Mark Twain and ‘Running for Governor,’ ” Su Wenjing, a comparative literature professor at Fuzhou University, said in a telephone interview. “And everyone remembers the specific cultural moment and social critique represented in the story, this is certain.”

Published in the literary magazine Galaxy just after the New York gubernatorial election in 1870, “Running for Governor” is a satire that takes aim at what Twain saw as the hypocrisy of the American electoral process and the dog-eat-dog nature of party politics. In the brief yet imaginative sketch, Twain finds himself nominated to run for New York governor on an independent ticket, only to be overwhelmed by a slew of false ad hominem attacks from several unnamed accusers.

More Zhejiang demolitions; overseas Christian books banned from Amazon-like site

ICC Note:

The article discusses the ongoing church demolition in Zhejiang province, China, and the government’s action in limiting the online selling of overseas Christian books. Last month, the government also stopped the Amity Foundation, the largest printer for Bibles.

05/15/2014 China (ChinaAid)- Two more churches were demolished in China’s coastal Zhejiang province last week in a continuation of the province’s campaign to demolish “illegal structures,” and persecution has spread to the web.

Less than two weeks after Sanjiang Church, a large Protestant church, was demolished in Yongjia County, Wenzhou, and less than one week after numerous other demolitions in Zhejiang, authorities tore down Shangwan Church and Hebin Churcn in Longwan District, Wenzhou (see http://www.chinaaid.org/2014/04/zhejiang-christians-fear-sanjiang.html and http://www.chinaaid.org/2014/05/more-zhejiang-churches-report-threats.html).

On May 8, authorities arrived at Hebin Church and claimed the church building was an “illegal structure.” Believers said that construction workers completely razed and cleared the site in just two hours. Then, Shangwan Church, which was built in 1868, was demolished on May 9 in drizzling rain.

Chinese Government Limits Online Selling of Christian Books已关闭评论

Posted in Headlines

Tagged Christian, Religious Freedom

They don’t scare easily, and they will take any client — not just dissidents. The Communist Party has noticed.

BY ALEXA OLESEN MAY 16, 2014

If there were a checklist for China’s “diehard lawyers faction” it would probably read something like this: Must be combative, dramatic, and have a flair for social media; must not be intimidated by authority; and must be willing to spend time under house arrest or in jail.

While there is no official group by this name, the term has evolved over the last few years to describe a particular type of criminal defense lawyer: brash, and determined to take on defendants whose rights, the attorneys believe, have been violated. The phenomenon came into sharp relief after the arrest of prominent Beijing lawyer Pu Zhiqiang (pictured above) on May 6 for allegedly “picking quarrels” by commemorating the victims of the June 4, 1989 crackdown on pro-democracy demonstrators in Tiananmen square in central Beijing. Pu remains in detention in Beijing, awaiting a hearing.

It all started with a case gone awry.

It all started with a case gone awry. Beijing lawyer Yang Xuelin, who identifies himself on social media website Weibo as a “diehard,” told Communist Party mouthpiece newspaper People’s Daily that the term originated from a discussion with another attorney in Guiyang, the capital of Southern China’s Guizhou province, in July 2012. Yang and a colleague named Chi Susheng were part of a team of lawyers from around China who had come to the city to defend a former property tycoon accused of gang-related crimes. Over lunch on the first day of the trial, the paper explained, Chi complained the trial was already not going well. It was riddled with procedural problems, she said, and the team was going to have to “firmly fight to the bitter end,” using the northern slang term sike — which roughly means to fight to the bitter end, or to die hard. (The tycoon was sentenced to 15 years in prison.)

PU ZHIQIANG08.10.06

The weekend of June 3, 2006, was the seventeenth anniversary of the Beijing massacre and also the first time I ever received a summons. It happened, as the police put it, “according to law.” Twice within twenty-four hours Deputy Chief Sun Di of Department 1 of the Beijing Public Security Bureau ordered me—“controlled” me, in police lingo—to go to the Fanjiacun police station in the Fengtai District of Beijing. This “practical action” of the Chinese government, although it violated basic human rights, was taken in support of the “stability” that the violent suppression at Tiananmen had brought about.

I recall the early hours of June 4, 1989. The few thousand students and other citizens who refused to disperse remained huddled at the north face of the Martyrs’ Monument in Tiananmen Square. The glare of fires leaped skyward and gunfire crackled. The pine hedges that lined the square had been set ablaze while loudspeakers screeched their mordant warnings. The bloodbath on outlying roads had already exceeded anyone’s counting. Martial law troops had taken up their staging positions around the square, awaiting final orders, largely invisible except for the steely green glint that their helmets reflected from the light of the fires. It was then that I turned to a friend and commented that the Martyrs’ Monument might soon be witness to our deaths, but that if not, I would come back to this place every year on this date to remember the victims.

PUBLISHED ON THURSDAY 15 MAY 2014.

Printable version PrintSend this article by mail Send français

Journalist and activist Wu Wei, a former Beijing based reporter for the South China Morning Post, reportedly arrested by Beijing police, has not been heard from by family or friends for several days.

Several Hong Kong media outlets reported the arrest, based on messages published on the Weibo social network, then relayed by journalist and blogger Wen Yunchao. No information has been released on why she would have been arrested. But the action may stem from her support for the release of human rights advocate Pu Zhiqiang.

Reporters Without Borders demands an immediate explanation from the Beijing government.

The news followed by one day the arrest of Xiang Nanfu, a regular contributor to the Boxun news website. Several days before that came an official announcement that journalist Gao Yu had been placed in criminal detention. She has not been heard from for more than one week.

“As in the case of Gao Yu, the fact that a committed journalist such as Wu Wei has not been heard from is of the utmost concern,” said Benjamin Ismaïl, head of the press freedom organization’s Asia-Pacific desk. “All the more so because the police are stepping up the pace of kidnap-style arrests as the anniversary of the Tienanmin Square events approaches.”