By EDWARD WONG JULY 26, 2015

Protesters in Hong Kong demonstrated the detention of Pu Zhiqiang, a civil rights lawyer from Beijing charged with “picking quarrels.” Credit Philippe Lopez/Agence France-Presse — Getty Images

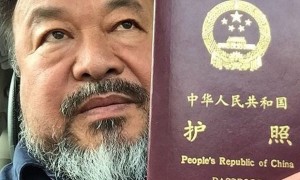

DUNHUANG, China — An oil-field worker in this Gobi Desert town posted poetry online memorializing the victims of the Tiananmen Square crackdown. An artist in Shanghai uploaded satirical photographs of his wincing visage superimposed on a portrait of the Chinese president. A civil rights lawyer in Beijing wrote microblog posts criticizing the Communist Party’s handling of ethnic tensions.

In each case, the men were detained under a broad new interpretation of an established law that the Chinese authorities are using to carry out the biggest crackdown on Internet speech in many years.

Artists, essayists, lawyers, bloggers and others deemed to be online troublemakers have been hauled into police stations and investigated or imprisoned for “picking quarrels and provoking trouble,” a charge that was once confined to physical activities like handing out fliers or organizing protests.

The increasing use of that law to police online speech, which appears to have become more common in recent months, is a piece of President Xi Jinping’s strategy to deploy the legal code to silence dissent and clamp down on civil society.

Since a Communist Party conclave last October, when Mr. Xi and other leaders emphasized “rule of law,” the government has introduced a series of new laws to tighten the vise over civil society and rein in foreign organizations, which the party fears could help foment a revolution here.

“The core of rule of law is that the government shall be restricted by law,” said Zhang Qianfan, a law professor at Peking University. “But now it is using the law to punish whoever criticizes it or has some influence in the public realm.”

In March, five young feminists using social media to organize a campaign against sexual abuse were detained and initially investigated on the picking quarrels charge, setting off global outrage against China.

The latest wave of detentions of so-called provocateurs took place this month, when police officers across China rounded up more than 200 civil rights lawyers and their colleagues. Some remain in detention and may be charged with picking quarrels and other crimes.

An article in People’s Daily, the flagship Communist Party newspaper, accused them of organizing protests and using instant messages to “engage in agitation and planning.” Global Times, a party-run tabloid, said the lawyers “often were no longer engaged in law, but in picking quarrels and provoking trouble with a plainly political slant.”

The legal definition of “picking quarrels” was expanded in late 2013 by the nation’s top legal bodies, the Supreme People’s Court and the Supreme People’s Procuratorate, to encompass online behavior. The court said the charge could apply to anyone using information networks to “berate or intimidate others” and spread false information. First-time offenders can be sentenced up to five years in prison.

The Dui Hua Foundation, a human rights advocacy group based in San Francisco, said that the interpretation was a “major elaboration” on the charge and that it treated online space “not only as a platform through which to incite others to disrupt social order but as a kind of public space itself that can be thrown into disorder by certain kinds of acts.”

The expanded interpretation also made unlawful any “defaming information” that is reposted 500 times or viewed 5,000 times, actions generally beyond the control of a post’s author. That definition was reiterated in the draft of a cybersecurity law released this month.

Dui Hua said in a March report that since the new interpretation took effect, “a growing list of Chinese people have been detained or charged for speech-related incidents” under the law. Among other things, the charge has been used to reinforce an “anti-rumor campaign” aimed at silencing people who question the official versions of news events.

For detail please visit here

A file photo of Gao Yu speaking in Hong Kong.

A file photo of Gao Yu speaking in Hong Kong.