Nov 23rd 2015, 13:58 by A.C.

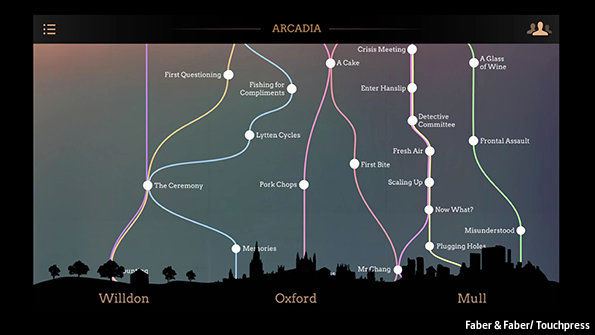

IAIN PEARS’s new novel “Arcadia” comes as a 600-page hardback, as befits the current trend for literary doorstoppers. But that’s not how the book was conceived and written. “Arcadia” the app, came first, and is another creature altogether. The e-novel gathers up ten characters in three different worlds, and presents them as a skein of coloured, intersecting lines. Short bursts of text propel the characters onward, or across into another storyline: the choice depends upon the reader.

IAIN PEARS’s new novel “Arcadia” comes as a 600-page hardback, as befits the current trend for literary doorstoppers. But that’s not how the book was conceived and written. “Arcadia” the app, came first, and is another creature altogether. The e-novel gathers up ten characters in three different worlds, and presents them as a skein of coloured, intersecting lines. Short bursts of text propel the characters onward, or across into another storyline: the choice depends upon the reader.

This is not a standard “choose your adventure” book, however. Mr Pears, the best-selling author of “An Instance of the Fingerpost”, had a more radical project in mind. What is unique about “Arcadia”—and intriguing as an experiment in interactive fiction—is the fact that each reader experiences the story differently. Mr Pears controls the story universe, but how readers weave the three tales—pastoral utopia, 1950s Oxford and dystopian future—is deeply individual. “There are readers who are ‘acrossers’ and others who are ‘up and downers’,” says Henry Volans, director of Faber Press, a division of the app’s publisher, Faber & Faber. “It’s meant to be a rabbit hole that encourages all sorts of reading.”

Until now, most e-reading has been static, or pepped up with audio or video enhancements. Mr Pears’s attempt to break from the physical page is subtle, but nonetheless bold. His time-travelling tale is, among other things, a metafictional meditation on storytelling. What is cause, what effect? Do we make our stories, or do our stories make us? Its digital form brilliantly expresses the parallels, overlapping paths and coincidences that are his story’s subject. Reading forward, then doubling back, following a different character to a point where many paths cross, the reader experiences the same events through multiple eyes. Recognition brings a satisfying shock: a sort of enhanced déjà vu, as the story solders itself in the mind.

“Arcadia” is all the more noteworthy for the fact that large publishers have largely given up experimenting in this realm. Most have turned away from costly innovations that have not paid off, like enhanced e-books, focusing instead on using digital tools to support the broader reading ecosystem. The Kindle, for its part, has stopped evolving, as the book theorist Craig Mod recently glumly noted. The market for e-readers is so saturated that Waterstones no longer stocks the devices. Publishers prefer to explore new ways to marry print and digital. Melville House has a line of “illuminated” novels with QR codes that lead to extra digital content; Picador published “The Kills” in 2013, a “digital-first” thriller that links to online films from characters’ points of view. FSG’s “The Silent History“, a multi-author 2012 serial story in an app, is marketed now as a print novel. Random House, meanwhile, offers a straightforward series of classic stories for mobile phones called “Storycuts“.

This leaves writers and artists to play digitally on their own. The first chapter of David Mitchell’s new novel, “Slade House,” is told in Tweet-length pulses; Jennifer Egan used the platform to serially deliver her story “Black Box”. Neither, however, exploits Twitter’s unique form of public conversation. The same can be said of Wattpad, a site on which writers upload works in progress; for all its millions of users, the fiction it inspires is not especially interactive. Its chief value is as a springboard, as British author Emily Benet learned when 2.2m Wattpad followers helped to land her a publishing contract.

Unsurprisingly, it is creative startups that are experimenting most boldly. The Circumstance art collective in Bristol will soon publish a new version of “These Pages Fall Like Ash”, a combination of a print book and an urban-walking app that overlays an imaginary world onto the physical. “Abra” is a fine book and an app that makes poetry magically form and reform. Software developers, meanwhile, are cooking up apps that combine narrative with games. “Gone Home” is a mystery in which the reader/viewer enters an empty mansion and follows clues to unlock text that tells the story of the vanished occupants. In “Device 6“, readers puzzle out a similar mystery chapter by chapter. Such “story exploration games” reveal narrative through gamelike moves, adding graphics to the text-based genre known as interactive fiction (IF).

Many believe this is the real future of electronic literature. If it’s hard to imagine a truly digital novel, it is because “we already have digital narratives—they’re called videogames,” argues Lincoln Michel of Electric Literature, a web site. Naomi Alderman, an award-winning British novelist who is also the author of “Zombies, Run!” a jogging app that has sold 2m copies, concurs. “There’s nothing like a novel to take you into the individual consciousness of a writer. But there are things that are choice-based that only video games can do.”

New narrative games like the prize-winning “80 Days“, based on Jules Verne’s “Around the World in Eighty Days”, allow players to experience a story not just as reader, but as protagonist. In these graphically rich narrative worlds, readers both lose and gain. What’s lost is our own imaginative rendering of a story world—arguably literature’s most distinctive feature. But what is gained is a truly empathic connection with the protagonist. “It’s about complicity,” Emily Short, a noted IF writer and critic, recently observed at the London Literature Festival. “You are in the position of being the idiot going into the basement, instead of the one shouting at the screen.”

Homo sapiens has always been a storytelling animal; so is homo digitalis. The difference is that in the digital environment, reading breaks the page, says Tom Abba, a scholar of digital narrative at the University of the West of England. “We’re trying to nudge the reader into a new kind of relationship with the story,” he says. In other words, better hold on: the digital ride is just beginning.

Source: http://www.economist.com/blogs/prospero/2015/11/interactive-fiction